Introducing Playdough

Today in a Facebook group, a parent of a 12 month old asked for the best playdough for a child who still puts everything in their mouth. Lots of parents and teachers in the group had great advice:

They recommended edible options like

- edible gluten free playdough made from baby rice cereal, applesauce and cornstarch

- pudding cup playdough from pudding and corn starch

- marshmallow, corn starch and coconut oil playdough

- or 25 edible play-dough recipes

Note: just because they’re edible doesn’t mean you should let your child eat them! The point of using these, in my mind, is to help children learn NOT to eat their art supplies, but if they do mouth these, you don’t have to worry about it.

Many preschool teachers said to just use any good homemade playdough recipe with no toxic ingredients. (Here’s my favorite playdough recipes.) Some of these have A LOT of salt in them, so it wouldn’t be good for kids to eat much of them, but they won’t, because they taste nasty. A couple tastes and they’re done, no harm done.

But a few respondents to this Facebook post said things like “I wouldn’t recommend playdough till they are around 3 or 4 when they know not to eat anything you put in front of them.”

There are so many benefits for young children in playing with playdough. (Read about the benefits of playdough and more on the power of playdough.) I think it’s ridiculous to deprive them of years worth of that experience because of the worry that they’ll mouth or maybe swallow a few tablespoons of non-toxic ingredients.

And besides, learning not to eat non food items is a good thing to learn! And playing with non-toxic playdough is a great place to learn that.

Now, I wouldn’t introduce playdough for the first time by setting some on their high chair tray and walking away. Of course they would eat it! (Maybe especially if it’s made of marshmallows…) However, you can absolutely introduce playdough to a young toddler – one year old is perfectly appropriate. The first few times, you sit right there with them, showing them this exciting new thing and showing them how to interact with it. Role model – tell them what to do. (Don’t even say “don’t eat it” because they may not even think of putting it in their mouth till you say the word eat. Children are new to language, and may hear “eat” and not hear the “don’t” part of the sentence.) Play with it, explore it, then put it out of reach when you need to walk away. If they do begin to move it toward their mouth, that’s when you would say “oh, yuck, don’t eat that. It tastes icky.” And make your icky taste face. That usually does the trick. If they end up with it in their mouth, just say, “oh yuck – let’s spit that out.” And then gently say – “let’s put this away for now, we’ll try again another time.” (It’s a good time to put it out on a tray or plate the first time so if you need to remove it you can.) With clear guidance, toddlers can learn to use playdough appropriately, and then have access to all the great learning that can come from playdough activities.

This whole topic just brings me to a larger topic.

Building Fine Motor Skills

In order for children to learn skills, they have to be able to have hands-on experiences with things. Almost everything they interact with could potentially have some risk. But often the chances are small. And with supervision and playing alongside, we can reduce the risk of severe injury to extremely unlikely.

In order for children to learn fine motor skills, they have to be allowed to use them! That means they need to be allowed to explore small items that they have to use the pincer grasp to pick up. Some of that happens with eating finger foods – peas and cheerios and slippery diced peaches all provide lots of pincer grasp practice. But children also need to be able to practice things like threading beads onto a pipe cleaner and once they’ve mastered that, threading beads onto string. They can practice things like dropping pompoms into a water bottle or putting buttons into slots cut in a plastic lid.

I do developmental screenings with parents – the 9 month old questionnaire asks if the child can pick up a string, the 18 month old asks if they can draw a line with a crayon or pencil, and the 22 month old asks if they can string beads or pasta on a string. I can’t tell you how many times the child hasn’t met that milestone and parents have said they just have never done anything like that with their child where their child handles small objects. Often they have avoided this because of fear of choking.

What about choking?

Yes, it is well worth being aware of the risks of leaving your child unattended with small items that they could choke on. And, it’s absolutely a good idea for all parents and all caregivers to be familiar with choking rescue. (Here’s a video.) And it’s good to know infant and child CPR too, just in case. (Videos of infant CPR and child CPR.) But this doesn’t mean that you should never let your child touch anything smaller than their fist.

Introducing Fine Motor Activities

Toddlers can do all sorts of fine motor activities with small objects. Like with the playdough, do a really good and intentional job of introducing the item under close supervision. Use role modeling and demonstration to be sure they know what to do with the items, and if they start to do inappropriate things with the items (like put a bead in their nose or in their ear), then we correct that. (Note: I do sometimes count how many of an item I put out, so that when I clean up I make sure I can account for all of them – if not, I search the floor to see if one just rolled away.) After they’ve interacted with an item safely multiple times, you can let them play with it more independently. I also do this approach with food – I don’t slice up grapes for my child. Instead, the first time I introduce grapes, I sit down with them and show them a grape and show them how I take one little itty bite out of the grape and chew it up, then take another itty bitty bite… Once we’ve practiced this multiple times, they can eat grapes independently.

Why Fine Motor Skills Matter

If we don’t let our children have this fine motor practice, then they’re going to be missing important development. Children need fine motor skills and finger strength to be ready for kindergarten tasks like writing, using scissors and turning pages in a book. They need them for self-care tasks like: buttoning a shirt, tying shoes, eating with a spoon, and opening food packaging. They need them to play with toys at preschool and not be frustrated by their inability to do things other children can do.

Fine Motor Development

These sample activities offer ideas for what sorts of things your child should be capable of at each age;

- 3 to 6 month olds – give them small toys that they can practice passing from one hand to another or hold them and shake them. Hold your baby on your lap and place a toy on the table in front of you that they need to reach for.

- 6 to 9 months – show them how to clap their hands or give high fives, they start “raking” things toward them, so try something like ping pong or whiffle balls or baby toys or finger foods like cheerios, take toys out of a container

- 9 to 12 months – continue to offer finger foods, encourage them to try picking up a block and putting it into a cup, encourage them to try picking up a string or a noodle, show them how to bang two toys together, wave bye-bye

- 12 months – build simple towers by stacking two or three items, let them scribble, practice eating with a spoon, turning pages in a board book, take off socks and shoes

- 2 years – practice using a fork and drinking from a cup, put on lids and take them off, string beads on yarn, show them how to draw a line, build a tower 8 blocks tall

- 3 years – button and unbutton clothes, use scissors, draw shapes, make a cheerio necklace, place coins in a piggy bank

Fine Motor Activities for Toddlers to Preschoolers

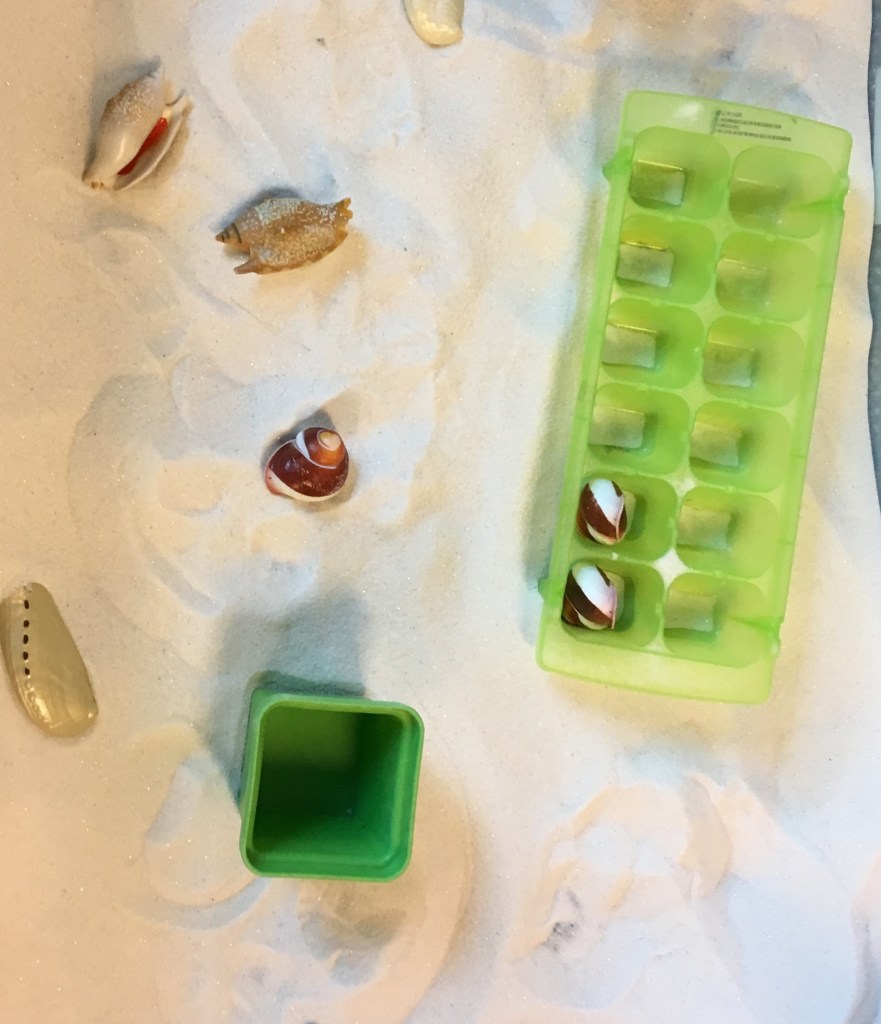

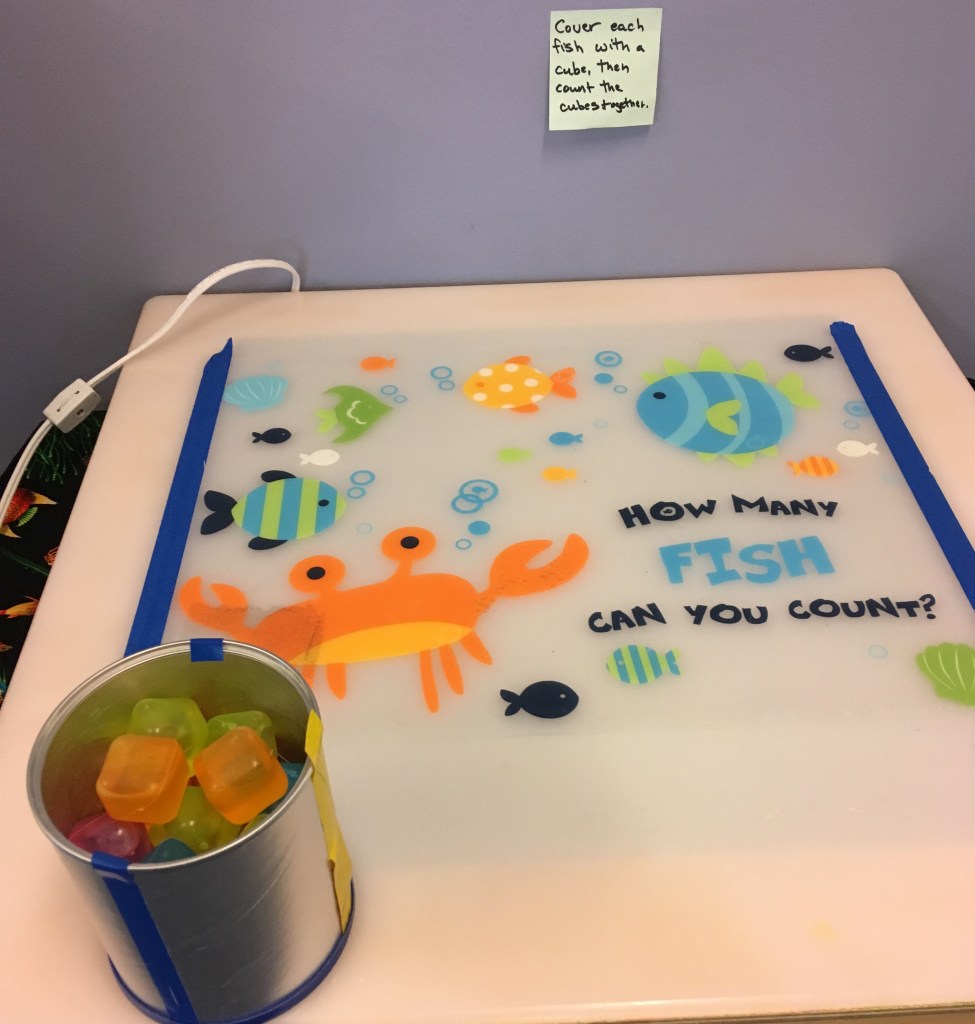

The pictures above are a random collection of activities we have done at our parent-toddler class for children ranging from 12 – 24 months old. Here are more ideas:

- Play with playdough: for the youngest child, this is smushing it with their hand or poking it with a finger. Then pulling it apart into smaller pieces. Then you can introduce tools to squish it flat (rolling pin), or cut it (plastic knife, cookie cutters) and so on. Hide small toys inside the playdough that they have to unearth.

- Shape sorters and puzzles: start with big and simple shapes, get more complex as they are ready for that.

- Build with megablox, then Duplos, then Legos.

- Twist pipe cleaners into shapes. Insert pipe cleaners into the holes on a colander.

- Dress-up clothes: put on gloves, zip zippers, fasten snaps, button buttons

- Stringing Beads (or pasta or cheerios): first, putting BIG beads on a stick or dowel, then medium beads on a pipe cleaner, then small beads on a string.

- Drawing: first scribbles, dots, lines. Later: Draw pictures, trace letters, color inside the lines.

- Collage: For a one year old, I use contact paper – take off the backing and leave the paper sticky side up – they can stick on pompoms, feathers, small pieces of paper… As the child gets older, have them practice putting glue on paper, then carefully sticking on small items like gems and googly eyes.

- Painting – first, just glop paint (or shaving cream or an edible substance like pudding) onto paper or foil or a plate and let them smear it around with their whole hand. Later show them how to paint with one finger. Then with a brush with a large handle, then a small handle.

- Filling containers: pick a small item (baby socks, pompoms, cotton balls, plastic lids, clothespins, dried beans, dowels, straws, q-tips, raw spaghetti, etc.) and a container to put it in (muffin tin, ice cube tray, jar with a big opening, water bottle with a small opening, boxes, a cardboard box with a small opening cut into it, a container with a plastic lid with a slot cut into it, a spice container or parmesan cheese container with small openings in the lid, a colander turned upside down). For one year olds, you’ll choose larger not-chokeable items that are easy to pick up and containers with large openings. For older children, smaller items and smaller openings. Once they’ve mastered putting items in with their fingers, let them use tongs or tweezers.

- Pick berries. Pull weeds or pick carrots – you need to pull just hard enough but not too hard, so it’s good for practicing how much strength to use.

- Sensory bin play – read my Ultimate Guide to Sensory Tables

- Water table play – read my Ultimate Guide to Water Tables

- Just go to pinterest or Instagram or google and search for “fine motor activities for toddlers” and you will have thousands of ideas. Don’t be afraid to try them! With you alongside as they learn, your children can safely explore and discover all sorts of wonderful things.