For parents who are wondering why their child interacts with the world differently than some other children do, and are wondering whether it might be autism, it can be hard to understand all the different ways that autism might present. This post is intended as an overview of: the clinical definition of autism, understanding what “the spectrum” means, some of the signs and symptoms of how autism might present, information about screening and diagnosis, and resources to support parents of neurodiverse kids.

The Diagnostic Definition

When I was a kid, we tended to think of autistic people only as the people who showed significant impairment in multiple domains: non-verbal, developmentally delayed, frequently stimming (e.g. rocking, flapping their hands).

Then there were a bunch of other kids who were skilled in many areas, but had some unusual behaviors. We called them “quirky” or “odd ducks” or said they “march to the beat of their own drummer.”

Then the term Asperger’s syndrome appeared, and was often applied to kids who were gifted and “quirky.” And we would ask questions about people like “where are they on the spectrum” or “are they low functioning or high functioning?”

Now, Asperger’s is no longer a distinct diagnosis. It’s been pulled back under the umbrella of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). And we’ve acknowledged that often people are “high functioning” in some areas while having a lot of challenges in other areas.

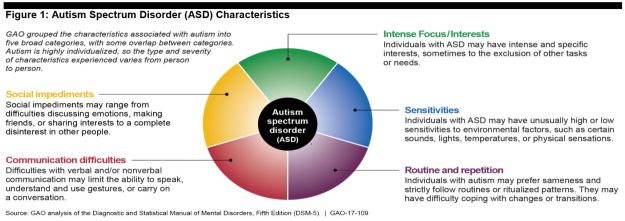

Here are the criteria for an ASD diagnosis in the DSM-V, which require showing symptoms in both of these categories:

A) Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction (deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction and in developing, maintaining, and understand relationships) and

B) Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities (as manifested by at least two of: Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech; Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns of behavior; Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus; Hyper- or hypo-reactivity to sensory input.)

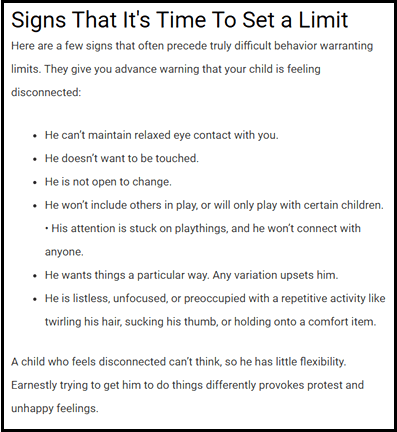

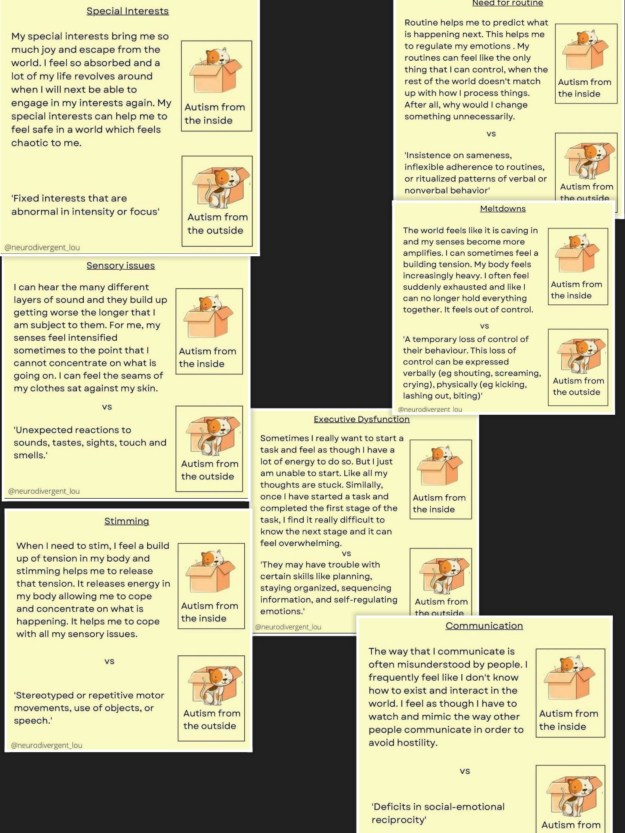

That is very deficit-based language. Here is another way to describe the criteria: A) may have challenges interpreting and following the same social rules and communication styles as their neurotypical peers or expressing / responding to emotions in the same ways that neurotypical people might and B) use repetitive movements, have strong preferences for predictable routines, and intense special interests. Reactions to sensory input and external demands may be more intense than typical.

I really like these images from @neurodivergent_lou that translate the diagnostic criteria which view autism from the outside into strength-based, empathy building views of what autism feels like from the inside perspective of an autistic person.

How Common is an Autism Diagnosis?

About 1 in 36 children is diagnosed with autism. (1 in 44 adults.) Within the diagnostic criteria, there’s a range of behaviors from subtle to extreme, and the impact on school and home ranges from minimal accommodations to major impacts.

What is a spectrum disorder?

When autism is described as a spectrum, it doesn’t mean this. (source)

Or this (source)

Autism is a complex way of interacting with the world that can’t be described on a simple numeric scale, and can’t be simplified to either “not a problem” or “tragic”.

I’ll share a few different ways that it has been illustrated, so you can find the one the best resonates with your experience.

The autism spectrum can look something more like this:

(That image comes from this great comic on “Understanding the Spectrum” by Rebecca Burgess – I highly recommend reading it.)

This graphic (source) breaks the spectrum into five categories, similar to Burgess, though the colors and the way they break things out are a little different:

And they explain that “the type and severity of characteristics varies from person to person” as seen in this diagram of three individuals’ ‘spectrums.’

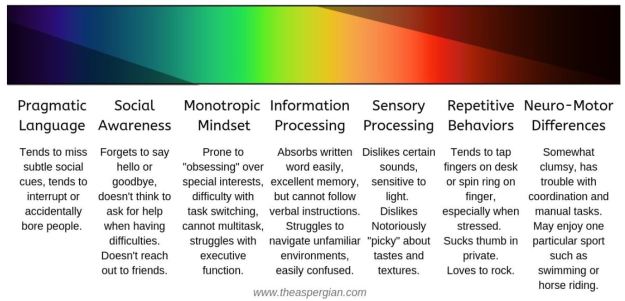

C.L. Lynch on theaspergian.com uses this illustration

Then gives a few examples of how this would apply for an individual person.

I don’t know which one of these graphics might be helpful for you, but I find it very helpful to think of these more nuanced descriptions rather than a single axis of “a little quirky” to “tragic.”

I know that if someone asks me if my youngest is “high functioning” or “low” or asks “how autistic is he”, I would find it difficult to answer those questions. It’s much easier to tell you – “here are the things he’s good at, here are some behaviors he does that might seem odd to you but don’t harm anyone or anything, and here are some challenges he has and some accommodations you could make that might help him to manage them.”

More Zones to Consider

The DSM-V criteria are two-fold: a) social-emotional differences, and b) restricted, repetitive patterns.

You’ll notice in the illustrations above that they each split the signs of autism a little differently, but here are some of the typical patterns that some autistic people might display. [Note that all autistic people are individuals, so any individual may have some of these signs and not others. As a parent, I found that if I went down any checklist of signs, I had many that I said “nope, that doesn’t describe my kid” and others where I went “ooh boy – that is exactly what I see!”]

- Social-emotional: may have challenges reading social cues, inferring what behavior is expected in a social situation, expressing their emotions in the same way a neurotypical person might expect them to or understanding / responding to other people’s emotions. Some may avoid eye contact. May be content playing / working by themselves and not appear to need the same social connections that others might. (Or might long for social connections and be very sensitive to rejection.)

- The Floor Time approach to child-directed play can help an autistic child connect with others in play.

- Sensory Processing: some autistic people may be hypo-sensitive to stimuli; many may be hyper-sensitive.

- Tactile stimulation (like tags on clothing or seams on socks or being touched) may distract and distress them. Or, they may seek tactile input, banging their heads on the wall, pressing up against others, wanting lots of hugs and loving weighted vests and blankets.

- Some may have lots of oral sensory issues. They may be super picky eaters or may gag easily. Others seek sensation, sucking and chewing on a variety of items.

- Many autistic people can get overwhelmed by sounds – they may be less able to filter out all the noise that neurotypical people ignore (traffic on the road, the hum of the refrigerator…) and may be happiest with wearing noise cancelling headphones in loud situations.

- Emotional regulation challenges: may have bigger reactions to a situation than typical. This could mean being so excited they bounce up and down, gallop around or flap their hands because the joy is too great to contain. It can mean meltdowns where too much stimuli, too many demands, or big disappointments overwhelm them and they react by screaming, hitting, or other behaviors for a prolonged period of time. (Note: the Zones of Regulation tools can be very helpful for autistic kids to work on emotional regulation skills.)

- Preference for routine / difficulty adjusting to changes and transitions. Many thrive in an environment with lots of structure, and very predictable routines. When a transition between activities is coming, they need a little more warning that it’s coming and help letting go of one thing and moving on to something new. Sometimes even with all the help you can give, an unexpected change or hard transition from a beloved activity to anything else can cause big meltdowns.

- Specialized Interests: A common characteristic is long-lasting, all-consuming interest in specific topics, whether that’s dinosaurs, astronomy, flags, Rubik’s cubes, or collecting memorabilia. When they start to talk about that topic to someone, it may become a prolonged monologue where they may not recognize when the other person has lost interest and is ready to move on, because they cannot imagine ever losing interest in that topic. They may also love repetition and repetitive movements.

- Impulse control and executive function may be harder for some autistic people. Discipline techniques that work with neurotypical kids may not be as effective with autistic children. (I find the Incredible Years and Ross Greene have the most helpful approaches.)

- Language / communication: some autistic people are less verbal or non-verbal.

- Motor skills: some autistic people may have motor challenges, ranging from “clumsy” to limited ability to control their movements,

Not everyone who shows a few of these behaviors is autistic. And not everyone who is autistic will have all these characteristics. And any one of these characteristics can manifest in subtle, barely noticeable ways or can be blatantly obvious to the casual observer. Again, autism is a spectrum disorder that can be a bit hard to pin down.

It’s also worth noting autism can present differently in girls and be more difficult to diagnose especially for gifted girls (my daughter who is gifted didn’t get diagnosed with autism till she was 20, because she was able to figure out how to “mask“).

Awareness vs. Acceptance

In much of our culture, autism is viewed in a very negative light. You’ll hear people talking about it as a tragic diagnosis, and people seeking a “cure” for their child’s autism, and using deficit based language. Even a supposed “advocate” may do so during events like Autism Awareness Month.

The Autism Self-Advocacy Network recognizes Autism Acceptance Month, which “promotes acceptance and celebration of autistic people… making valuable contributions to our world. Autism is a natural variation of the human experience, and we can all create a world which values, includes, and celebrates all kinds of minds.”

Autistic people have unique strengths. For example, many have intense attention to detail, a high degree of persistence, and ability to analyze data. Their “obsessive” interests can lead to stunning expertise in their chosen career fields. And “Sometimes being autistic means that you get to be incredibly happy. And then you get to flap. You get to perseverate. You get to have just about the coolest obsessions.” (Source)

A Note on Co-Morbidity and Social Issues

Autism also has several co-morbidities: conditions that often occur with autism. Many of the challenges we think of as being due to autism actually come from these co-morbidities. We should think of them as separate issues and handle them separately. “Over half of autistic youth [also had] attention deficit disorder (53 percent) or anxiety (51 percent), nearly one quarter had depression, and 60 percent had at least two comorbid conditions. Other common comorbid conditions include sleep disorders, intellectual disability, seizure disorders, and gastrointestinal ailments.” (Source)

And many of the “challenges” of autism actually come from societal attitudes toward autism and demands on children to “learn how to act normal”. For example, if a child jumps up and down with excitement, is that really a problem behavior that needs to be corrected? If a teenager gets overwhelmed by noises, so chooses to wear noise-canceling headphones in many situations, is there a reason anyone else should care about this? If someone can’t stand it when the different foods on their plates touch each other, isn’t it easy to use just a little extra care when dishing them up instead of using a lot of energy telling them that “you just have to learn to cope with that”? If the neurotypical community understood more about neurodiverse people, and made simple adjustments, it would greatly reduce the “challenges of autism.”

Screening and Diagnostic Testing

If you’re wondering about your child, or a child you know, start with this list of symptoms, or red flags to watch for. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/signs.html

If you’re still concerned about possible signs of autism, use a screening tool:

- For children under 2, check out Baby Navigator.

- If your child is 16 – 30 months old, try the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, available at www.autismspeaks.org/screen-your-child

- For birth to 6 years, use the ASQ-SE – Ages & Stages Questionnaire

- You may find other helpful tools here, such as AQ and CAST. https://www.autismresearchcentre.com/tests/

If you’re still concerned, talk to your child’s health care provider, and/or contact your state’s public early childhood system to request a free evaluation to find out if your child qualifies for intervention services. This is sometimes called a Child Find evaluation. If your child is under three years old, look at the ECTA website. If your child is 3 years old or older, contact your local public school system. Look here for all the details about how to access testing.

In King County, Washington, where I live and teach, some resources for diagnostic testing include: Kindering (especially for kids under age 3), UW Autism Center (this is where my daughter was tested at age 20), and Seattle Children’s Autism Center. Some private practice psychologists also offer testing. For example, our son was tested by Heather Davis at Brook Powers Group, who had worked with him in their Incredible Years program.

Here is a podcast with tips for what to do when you’re waiting for an autism diagnosis or a PDF on the same topic.

Are you debating about testing?

Some parents debate about whether or not to test. Or they test and end up with a diagnosis of “we can’t say it’s autism but we can’t rule it out.” They wonder about whether to seek out special education services. For more on those topics and on what to do while waiting for a diagnosis, check out my post on “Autism? ADHD? Delayed? Or just quirky?”

What was the Cause? Is there a Cure?

It can be tempting to ask “what causes autism” and for many parents, that’s a quest to understand whether they “did something wrong” that led their child to be autistic. There’s no one cause for autism. There may be genetic factors, or environmental factors, or a combination of environmental factors with genetic susceptibility. Personally, I have not found it helpful to look backwards and wonder about the cause – it’s better to focus on what we need to do to move forward into the future.

I also do not seek a “cure” for autism. (Because that implies it is a problem that needs to be fixed rather than just a different way of being in the world which benefits from accommodations.) Some parents spend a great deal of time and energy seeking a way to fix their child. There are some effective treatments which can help make things more manageable for the family, but there are also some “treatments” you’ll find on YouTube videos or random people’s blogs that can either cause harm, or simply just take more time, energy and money than they are worth.

For example, many parents have reported significant improvements in behavior problems with dietary changes. If you find diet changes that are generally considered nutritionally sound and they prove helpful for you, then hurray! But if a special diet is prohibitively expensive, or if it deviates from mainstream nutritional advice and might cause nutritional deficits, or if your kid is just a super picky eater and it’s a huge battle, it’s worth knowing that there’s not a lot of research that proves dietary changes are essential.

Resources on Autism

General Resource Guides

There are lots of resource guides from various organizations. Try these from the Seattle Children’s Autism Center, Autism Parenting Magazine, and the AAP. Plus these communication resources. Note: I have not vetted all these resources. If you discover any materials that approach autism as a terrible disease to be cured, or focus on ways to “fix” autistic kids, set those aside. I personally choose materials that talk about autism as a neurological difference that shapes who they are and how they interact with the world, and talks about ways we can increase accessibility for them.

Autism Navigator has a free online class (approx 3 hours) on Autism in Toddlers. They have handouts you can print on everyday learning activities, how parents can support language and emotional skills, and Q&A for parents.

Discipline and Behavior Challenges

- This article is short and helpful: 15 Behavior Strategies to Help Children with Autism.

- There are tons of helpful resources at challengingbehavior.org: visual schedules, tip sheets on making daily routines easier, handouts on teaching emotional IQ, addressing behavior like hitting or biting.

- If it’s available in your area, I highly recommend the Incredible Years program. (We worked with Shanna Alvarez in Seattle, who was fabulous.) While the parents meet, the kids attend “Dinosaur School” which teaches social and emotional skills. Note: my Discipline Toolbox is highly influenced by what we learned at Incredible Years.

- Ross Greene has some really helpful tools, summarized as “Kids Want to Do Well – If they’re not doing well, ask yourself what skill or resources they are lacking.”

- If emotional regulation is a challenge for your child, check out my post on Big Feelings and the Zones of Regulation approach.

Building Connections with Your Child

Floor Time, or Child Directed Play, is a powerful way to connect with any child, but especially children who have challenges with social-emotional connections. Click here to learn about Floor Time: child-directed play. On Autism Navigator, learn how to support social communication development, and transactional supports to promote learning.

More resources

There are helpful resources at https://brightandquirky.com which has webinars with leading experts on how to support kids who are gifted AND autistic (or have other behavioral issues).

And for your child, here’s my list of Children’s Picture Books about Autism and other “quirky kids” stories. Seeing themselves reflected in a book might be helpful for them.

If you’ve got one of those kids whose brain and body are always moving super fast, leaping from one thing to the next, make sure to check out my post on “the race car brain.” If you’ve got a shy child who observes more than they engage, check out my post on the slow to warm up child.