When you’re looking for child care, the choices can feel overwhelming. Here’s a five step process to help guide you through narrowing down your options.

- Learn the Basics

- Figure out exactly what you need

- Gather your options

- Research your top choices

- Make the decision

Then, once you’ve found a provider, there’s an on-going step… continuing to evaluate whether it’s still meeting your needs, and making changes as needed.

Step 1 – Learn the Basics

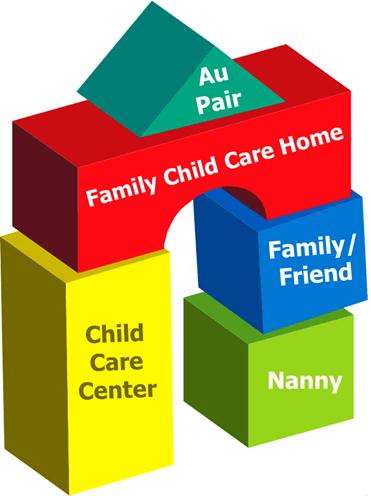

For an infant or young toddler, you may be considering options including: family or friend care, a nanny or au pair, a family child care in a home, or a child care center.

If you’re new to thinking about child care choices, start with my post on Child Care Basics which is an introduction to how each of these options works, just so you have a sense of what is possible. I talk about all of these options, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. Once you’ve got the basics, return to this article.

Step 2 – What do you need?

Before you start looking at specific options, think about your concrete needs / basic logistics. Think about your “can do” and “really can’t do” list. Start with these, because otherwise you might fall in love with a program and then discover that you can’t make the logistics work. (I know many people who have talked themselves into something, saying “it’ll be OK, I’m sure we can make it work” and then had to give up when it proved unsustainable and start all over with their search.)

Location

How far are you willing to drive? How far is your child willing to be driven (some children do fine in the car, others are miserable)? Does it make sense to choose a caregiver who can come to your home? A location near your home or one near your work? Is the location convenient for other family members or friends if you need them to pick up?

Schedule

How many days a week? Do you have specific days of the week you can or can’t do? What time do you need care to start and end? Do you need flexibility on the end time if you sometimes run late leaving work, or if you’re caught in traffic? Can your schedule change from week to week or is it pretty predictable?

Cost

What’s manageable? Cost ranges hugely, so think through carefully what is manageable for you, and don’t spend time looking at options that are outside your price point.

It’s important to know that lower cost doesn’t have to mean lower quality of care. There are some amazing childcare providers who provide lower cost care. Their buildings may not be as beautiful, their equipment might not all be shiny and new, but it’s all clean and well cared for. The key factor in excellent child care is the people who provide the care.

Some child cares offer a sliding scale based on parent income. Some states, municipalities, and tribes have child care subsidies available. Learn more at: https://www.childcareaware.org/families/cost-child-care/help-paying-child-care-federal-and-state-child-care-programs/

Step 3 – Gather Your Options

It’s worth looking at ads in parenting magazines and online but it’s also worth knowing that you’ll mostly see ads for large chains and expensive daycares, because they have money for ad budgets. To find the local, smaller, low cost options you don’t look at paid ads. You ask around – ask friends, family, co-workers, people in birth classes or parents at the park. If they say they LOVE a program, ask why! It could be that you’d love it for the same reason, or it could turn out that something they love would totally turn you off.

You can do web searches – some small day care providers can have a good web presence, but many don’t.

If you have local child care referral services run by non-profits or governmental agencies, use them! If the referral service is something that providers have to pay to be a part of, then it’s just another form of advertising, really, and again, you’ll get the larger chains and more expensive providers. But non-profits and governmental agencies may offer referrals to a much wider array of small providers.

Step 4 – Research your top choices

Once you’ve got a list of four or five possibilities, do more research. Read the program’s websites in detail, if they have one. Call to ask specific questions. Go to open houses or tours or ask to observe, if possible. Here are questions to consider:

Are there openings? What is the enrollment process?

What is the cost? When are payments due?

What is the schedule?

- What time could your child start? What time could you pick up?

- For infants: Are infants fed on demand? If your child is breastfeeding, how do they support that? Where do babies sleep? Are baby’s cries responded to promptly?

- For toddlers: How is time divided between activities? Play time? Quiet time? Outdoors? Snack? What activities are available? What do caregivers do to support the child’s learning? If meals will be provided to your child, when, where, and what will be included? Is there nap time – when? where?

- Are there days / times of year when care is not available? (holidays, caregiver vacations, etc.) What happens if a caregiver is sick?

Who are the childcare providers?

- Training: What is their training? Have they done safety training? Have they done additional training in supporting the child’s learning and development? Do they have and AA or BA in early childhood?

- What experience do they have?

- Do they participate in continuing education or other opportunities to improve their skills and the care they provide?

- Longevity / turnover. As a general rule, the longer the teachers have been there the better. (Unless you get the sense that they’re burned out and only there due to inertia….)

- Do they enjoy kids? Do they sit on the floor with the kids, smile, and engage with them? Or are they standing on the edges talking to other adults, occasionally calling out instructions to a child?

- For toddlers and older: How do they handle discipline? What are their rules and how do they reinforce them?

- For some families, it is important that caregivers share their cultural background or faith beliefs. Some families seek out diversity, such as a caregiver who speaks a different language than they speak at home. Meeting the caregivers may give you a sense of whether your goals will be met.

Who are the children?

- How many children? How many teachers? (In Washington state child care centers, the maximums for babies under one year old is four babies per adult, with a maximum group size of 8 babies and two adults. For 12-29 month old children, it’s 7 children per adult, max of 14 children in a group. But those are the maximums. Your child would get more individualized attention if there are fewer children for each adult to tend to.)

- What is the age range of the class? Some parents prefer that all the kids be as close as possible in age, but many programs point out the benefits of multi-age classrooms.

- What are the cut-off dates for age? Your child may do best if you choose a program where they are right in the middle of the age range rather than youngest or oldest. Many parents push their child ahead to the next program the second they reach the minimum age… but I don’t recommend this – if your child is always the youngest one in the room, they may often also feel like the slowest, least coordinated one in the room.

- In a child care center, how is the transition from one age group to the next managed?

What is the environment like?

- Is it clean? Safe? What are their policies for illness and cleaning? Where are diapers changed? For infants, are safer sleep practices followed?

- Is there a wide range of materials and supplies that are appropriate to your child’s age and abilities? Are materials in good condition?

- Are there areas for quiet play / resting and areas for active play?

- Is there an opportunity for time outdoors? What is that space like?

Parent Partnership

- Are parents welcome to visit any time?

- Can parents be involved in the program?

- Do caregivers share and talk to parents about their child’s daily activities, either at drop-off or pick-up?

- If parents or caregivers have particular questions or concerns, can they schedule a time to speak in depth (this may need to be at a time when the caregiver does not have children to care for)?

- How do providers work with parents to incorporate the family’s culture and values into the classroom?

- Can parents be involved in a child’s birthday celebration? special events? field trips?

Note: some facilities have cameras where parents can watch the child at any time. These are not essential – if you trust your caregivers and can visit at any time, these “nanny cams” shouldn’t be a big part of your decision making. Some facilities provide lots of written reports to parents, and while those can be nice, remember that time spent filling out reports may be time that could be spent interacting with your child. Having a quick moment to chat with the caregiver each day can be just as informative.

Licensing?

Licensing requirements vary by state and by type of child care provider. But, if they are licensed, you may be able to view their licensing records to see if there have been any complaints. (In Washington, use https://www.findchildcarewa.org/.)

Step 5: Making the Choice

After you’ve done your research on your options, if possible, don’t narrow it down to a single choice. If you fall in love with one and rule out all others, and then it turns out that one doesn’t have availability, that can be really stressful. Instead, make a list with multiple options, ranked from your favorite on down, and then contact your top choice. A lot of this process is intellectual and practical, comparing things like price and location. But in the end, sometimes it comes down to trusting your gut.

Vibe The most important thing you’re “looking” for is something you can’t see. How does it feel? Is it warm, nurturing, full of exciting learning experiences, and full of happy children and teachers? Or is it cold, disconnected, uninvolved? We know from the science of brain development that children learn best when they feel safe and are happy, so look for a place where they will be happy and engaged. You should also look for a place where you would feel great every time you drop them off to spend time there. That’s the one to choose.

On-Going

Even once you’ve found an option, the evaluation goes on… does it still seem like a good fit? If you have concerns, you can approach the caregiver to try to work them out. Sometimes things work out perfectly, and sometimes they don’t and you have to start the process again, so be sure to hold on to your notes, in case there’s a next time to search.

Resources for Families in Washington State

Financial Support: Options for paying for child care: https://childcare.org/family-services/pay-for-care.aspx and https://childcareawarewa.org/families/. Low income families (income less than $42K per year) can qualify for child care subsidies, including helping to pay a family caregiver. Learn more: https://www.dcyf.wa.gov/services/earlylearning-childcare/getting-help/wccc

Child Care Centers and Family Day Cares

- Washington State: https://www.brightspark.org/for-families/

- Child Care Check from WA State Dept of Children Youth and Families – for licensing information and quality ratings of child care centers (https://www.findchildcarewa.org)

- Elsewhere: https://www.childcareaware.org/

Nannies and Au Pairs

- Seattle Nanny Parent Connection Facebook Group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/SeattleNannyParentConnection

- Annie’s Nannies (http://anniesnannies.com/)

- Au Pairs: Info from Cultural Care (https://culturalcare.com/)

- Au Pair in America (http://www.aupairinamerica.com/state/washington.asp)