Gender is a complicated mix of our biological sex, how we like to dress and wear our hair, our interests, our identities, and what other people expect us to do based on their perception of our gender. In this post, I’ll address:

-

- When should we talk to kids about gender identity?

- Some vocabulary: biological sex, gender identity, and gender expression

- Defining your family values about gender

- What if your child is exploring gender expression and gender roles

- What if your child tells you they are transgender

- How you can show support to a transgender person

- What if your child asks about someone else’s gender

- Interacting with a transgender person

- Resources to learn more (including kids’ books on gender

When do we talk to children about gender identity?

You already have been! We probably started moments after their birth, with the first announcement of “it’s a boy” or “It’s a girl.” By 2 to 3 years, children begin to label themselves as male or female. By 3 – 4 years, they start categorizing things as “boy things” or “girl things”, and by 4, they may say “only boys can do that” or “girls never do that.”

So, young children are very aware of gender. Even if we avoided talking about it, they would absorb lots of messages from their environment. If we talk to them about it, we have the chance to share our own values with them, and to help to shape their understanding.

What is gender?

Let’s start with a few definitions.

Biological Sex: A person’s body parts / hormones. Can be categorized: male, female, intersex.

Gender Identity: A person’s own internal sense of who they are. (No one else gets to define this for them.)

Gender Expression: How a person chooses to dress, wear their hair, and behave.

Gender Roles: How other people expect someone to act, or what they expect them to be interested in, based on their perceptions of that person’s gender.

Those are all separate from sexual orientation. Gender is about who you are. Sexual orientation is about who you are attracted to.

Sometimes all these pieces line up just like cultural and generational stereotypes would predict, but sometimes they don’t. Many people are cisgender – their identity aligns with their biological sex. Some people are transgender – their internal sense of who they are (identity) does not line up with the sex assigned to them at birth. Others may identify as gender non-conforming, non-binary, genderqueer, or other variations. It is estimated that between 1 in 100 and 1 in 400 people are transgender. One way to think about it is that transgender folks may be about as common as redheads.

There are also many people who are cisgender, but don’t fit a stereotypical understanding of gender. In terms of gender expression, some women prefer to wear ‘men’s clothes” and some men like to wear dresses or makeup. In terms of gender roles, we all acknowledge that boys may like dolls and dresses, and girls might like trucks and baseball. We say women can be doctors, and men can be dancers. Yet, there is still surprise in our society when people run across a male preschool teacher or a female heavy equipment operator.

Defining Your Family Values about Gender

Parents are their children’s most important teachers. The way you talk about gender, and your unconscious actions, will shape your child’s early perceptions about gender. So, spend some time reflecting, and talking with the other significant adults in your child’s life (friends, family, faith leaders), to figure out what your family values are about gender identity, expression or roles. Then, pay attention to how you’re manifesting these values. Some things to consider:

- When buying clothes or toys for your child, or choosing activities to sign them up for, ask yourself: does my kid like things like this, or am I picking it because of gender? Does this choice expand or limit their choices and expectations about gender?

- If you hear your child (or other people in your child’s presence) make observations like “only girls wear pink” or “boys can’t do that”, ask them questions about why they think that, and talk about stereotypes and alternative views.

For more on gender, see: https://gooddayswithkids.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/gender.pdf

What if your child is exploring gender roles or expression?

During preschool and early elementary years, many children explore what it means to be a boy or girl, and they may try out different roles. Especially in pretend play, girls may try out being a dad, boys may try on “girly” clothes. This is a normal part of children’s play, and part of how they learn about their world and their culture. There is no need to discourage this.

Nor do you need to overly encourage it. Just because a boy tried on the fairy wings at school doesn’t mean you need to immediately purchase full princess wardrobes for home. (If, over time, he tells you he really really wants a princess wardrobe, that’s fine… but don’t feel like you need to jump in with both feet immediately. It may have been just a short term exploration.)

Don’t make assumptions about your child’s long-term gender identity or sexual orientation based on short-term interests or activities. Some children outgrow this and move on to gender expressions and roles that line up with their biological sex. Some continue to explore gender expression and gender roles, such as the “tomboy” who dresses and acts (expresses themselves) like a boy but still clearly identifies as a girl, or the teenager who may wear eyeliner and nail polish but identifies as male. Some people who blur these lines call themselves gender expansive or gender creative. However your child wants to express themselves, you can help them to feel safe and loved.

If children want to make non-stereotypical choices, some parents choose to inform them about what reactions they might encounter: “it’s fine to have a sparkly pink backpack, but some kids think that only girls like sparkly pink, so they might tease you.” Then if the child still chooses that, at least they had the information to prepare themselves for the response.

What if your child tells you they are transgender?

Gender identity tends to be firmly established by age 4. If a child occasionally swaps gender roles in pretend play, or tells you “I really like playing with girls’ toys” or tells you once or twice, “I wish I was a boy, so I could do that”, those are likely just short-term explorations.

There’s a big difference between that and a child repeatedly telling you that their biological sex does not match their internal identity. Transgender and gender non-conforming kids are: consistent, insistent, and persistent. They consistently identify as one gender, they don’t waffle back and forth. They are insistent about that identity and get upset when mis-identified. They persist – they identify this way over a long period of time. (Source)

If you are cisgender, you may find it challenging to really understand a transgender person. For me, as a cisgender woman, I have truly never questioned my identity – I’ve always known I was female, always been comfortable with other people treating me as female, and offended if someone mistakenly thought I was a boy. But imagine what it would be like if I felt that way as strongly as I do but I happened to have been born into a body with a penis. Imagine the challenges of that experience!

Transgender people often experience gender dysphoria, a distressing disconnect between the sex assigned them at birth, and their internal identity. Every time they look at their body, it feels wrong to them. Every time someone refers to them by the wrong pronoun, they may squirm inside. For some transgender people, this sensation is mild and manageable, but for many it is not. Transgender girls may talk about a desire to cut their penises off. Transgender boys may begin self-harming as their breasts begin to grow. Many transgender people (41%) attempt suicide, often to escape the pain of dysphoria.

If a child says they are transgender, we don’t need to know whether they will always identify that way. But, in that moment, we can listen to our children tell us about who they are, so we can provide the best possible support. Trying to change a child’s identity, by denial or punishment or whatever, doesn’t work, and can do long-term harm.

Amongst transgender people, rejection by their families can lead to depression and other mental health problems, homelessness, behaviors that put their health at risk, and suicide.

Family acceptance promotes higher self esteem, more social support, improved health, improved mental health, with reduced anxiety and depression, and a huge reduction in suicide attempts.

How you can show your support (for your child or others that you know):

- Assure your child that they have your unconditional love and support

- Use the name and pronouns that the child asks that you use (note: I don’t say their “preferred pronouns”. Their pronouns are their pronouns, that’s not like a preference for vanilla ice cream.)

- Ask that others respect the child’s identity

- If they ask to transition to a gender expression in line with their identity (e.g. clothes and hairstyle), many parents have followed the path of first trying it out at home, then trying it out on a vacation – what is it like to be out in public with that identity, then transitioning in their home community.

- If children ask for a medical transition, there are options: adolescents can take hormone blockers to delay puberty – these put on a “pause” button while they make long-term decisions. Taking gender hormones (e.g. testosterone and estrogen) can help to move biological characteristics to line up more with their identity, and most of the effects are reversible if the hormones are stopped. There are gender-affirming surgeries as well. These are not common for youth, but can reduce suicide risk for children experiencing severe dysphoria.

You can find many more resources at: https://www.hrc.org/search?query=transgender+children+and+youth

What if your child asks about someone else’s gender?

Young children are trying to make sense of their world, and one way they do that is by categorizing the people they see. If they think they’ve worked out an understanding of gender, but then see a person who doesn’t fit that understanding, they may ask questions – quietly, or at the top of their lungs. Remember that if your child asks a question about something, they are trying to understand it, and they may also be asking you if you think that it’s OK. (check out Jacob Tobia’s post on this)

So, your child might say “that boy is wearing makeup!” or “Why is that woman dressed like a man?” If you shush them, or avoid the topic, you imply to your child that what they have seen is bad or is a taboo subject. Try answering the question: “Yes, sometimes boys do wear makeup, and that’s OK.” Or “Yes, some women prefer to dress in men’s clothes. Or, that might be someone who identifies as a man, even though their body might look more like a woman.”

You can find some simple, matter-of-fact things you might say to a child about gender identity at http://muthamagazine.com/2014/01/mama-ella-has-a-penis-marlo-mack-on-how-to-talk-to-your-children-about-gender-identity/; and www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/its-not-that-hard-talking-to-children-about-gender_us_5899f3b0e4b0985224db5a3f

Interacting with a transgender person

Some other things you can do (and model for your child) about how to interact with someone who is (or may be) transgender:

- Use the language a transgender person uses for themselves. (He, she, they, or whatever.) Sometimes you may just wait till it comes up in conversation with those who know them. Or, if you don’t know what pronouns to use, you can ask – or even better, share your own pronouns. “Hi, my name is Janelle, and I use she/her as my pronouns.” If you make a mistake on pronouns, apologize briefly and move on.

- Some transgender people choose to medically transition, or change their names, or change their appearance, but some don’t. You (or your child) may be curious. Before asking questions, ask yourself “do I need to know this information to treat them respectfully?” and “Would I be comfortable if they asked me this question, or would I ask that question of any other person?” (So yes, it would help to know their name and pronouns, but there’s no need to know about the status of their private parts.) Some specific questions you would generally avoid: Asking their birth name, or asking to see photos of them from before they transitioned, asking what hormones / surgeries they’ve had, or asking about their sexual relationships.

- Someone’s transgender identity is their private information. It is not yours to share.

- Remember that you don’t have to understand their identity to respect it.

- You can’t necessarily tell if someone is transgender by looking at them. So, many people are working to be gender inclusive at all times. You can encourage this process by sharing observations. For example, if forms you’re filling out have two checkboxes for male and female, encourage the provider to instead ask for gender, and leave a blank space for people to fill in. If there are single stall restrooms at a facility, encourage that facility to replace the Men and Women signs with “Restroom” signs. If you notice a teacher frequently divides a group into “boys” and “girls”, encourage them to consider other options: “everyone wearing jeans”, or “everyone whose birthday is in January – June” or “everyone who likes cats.”

Learn more about how to be a trans ally: https://bolt.straightforequality.org/files/

Straight%20for%20Equality%20Publications/2.guide-to-being-a-trans-ally.pdf and https://transequality.org/issues/resources/supporting-the-transgender-people-in-your-life-a-guide-to-being-a-good-ally

Handouts

If you’re an educator who would like information to share with parents, I have created two handouts. Both address the concept of gender identity, defining your own values about gender, kids who explore alternate gender roles and transgender children. Choose between Gender as a Spectrum and Talking with Children about Gender Identity which adds info on how to talk with a child about gender non-conforming people you may encounter, and how to be supportive of transgender people.

Resources for More Information

Overview: www.genderspectrum.org/quick-links/understanding-gender/

How to Talk to Kids:

- www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/parents/preschool/how-do-i-talk-with-my-preschooler-about-identity

- Our Whole Lives Sexuality Education Videos: https://www.ucc.org/what-we-do/justice-local-church-ministries/justice/health-and-wholeness-advocacy-ministries/under-your-wing-our-whole-lives-sexuality-education-video-series/

Transgender Children:

- www.hrc.org/explore/topic/transgender-children-youth

- http://gendercreativekids.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Trans-Kids-Beyond-the-Myths-2016-1.pdf

Big list of resources: www.genderspectrum.org/resources/parenting-and-family-2/

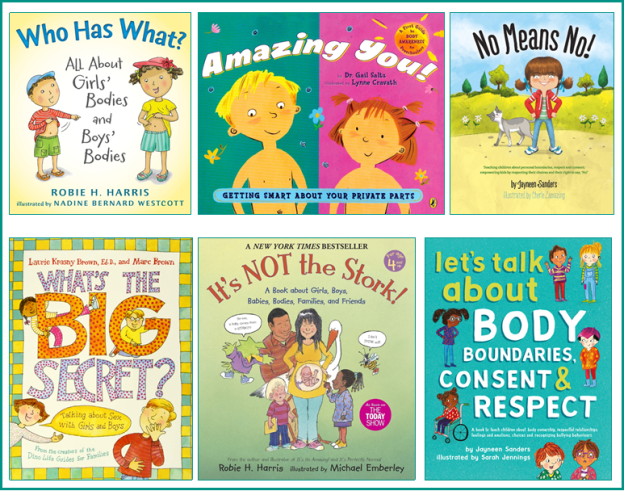

Recommended Children’s Books about Gender

Note: some of these books are about gender expression, some about gender identity, and some about gender roles. For example, Sparkle Boy and Jacob’s New Dress

are both about boys who like to wear dresses (expression) but both still identify as boys. 10,000 Dresses

is about Bailey, who wants to wear dresses and identifies as a girl, although others label Bailey as a boy. Made by Raffi

is about a boy who likes to knit even though others say that’s a girl activity (role). Decide what topic(s) you’re interested in exploring, and be sure the book lines up with that goal.

Also, lots of books on these feature non-human characters (like Introducing Teddy) and lots of them are metaphorical – they can be read as being about gender identity, but your child may not make the cognitive leap to understand that metaphor. For example, in Red: A Crayon’s Story

, a blue crayon mistakenly labeled as “red” suffers an identity crisis and in Bunnybear

, Bunnybear identifies as a bunny, and Grizzlybun identifies as a bear. If you’re just looking for books to encourage a general sense of acceptance of diversity and self-identification in your child, these are a great match. But if you want to specifically address gender identity, you will need to help your child see that message: “Remember that book we read, Neither

? It was about a creature that was both a bunny and a chick, but not quite a bunny or a chick? That’s sort of like our friend Rex, who told us they are both a boy and a girl, and not quite a boy or a girl? They said that’s called non-binary. And remember how Neither felt sad when nobody accepted them, but felt happy in the Land of All where they were accepted? Can we be a Land of All for our friend Rex?”

If I had to choose just one, I’d choose Who Are You? The Kid’s Guide to Gender Identity by Pessin-Whedbee. Age 4 – 8.

Here are recommendations for more options:

- https://booksforlittles.com/gender-spectrum/

- https://assets2.hrc.org/welcoming-schools/documents/WS_Great_Diverse_Books_Transgender_Non-Binary_Children.pdf

- http://www.mothering.com/articles/20-picture-books-strong-girls-sensitive-boys/

- http://gendercreativekids.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Trans-Kids-Beyond-the-Myths-2016-1.pdf

- https://www.scarymommy.com/books-gender-expression

- https://www.uua.org/files/2021-08/at_home_sex_ed_%20resources_grades-K-6.pdf