I wrote a full post about play-based preschool that provides an overview of how it works, and what the benefits are. This post gives specific examples of the types of activities you might find at a play-based preschool and has concrete examples what children learn from each.

Blocks / Building Materials

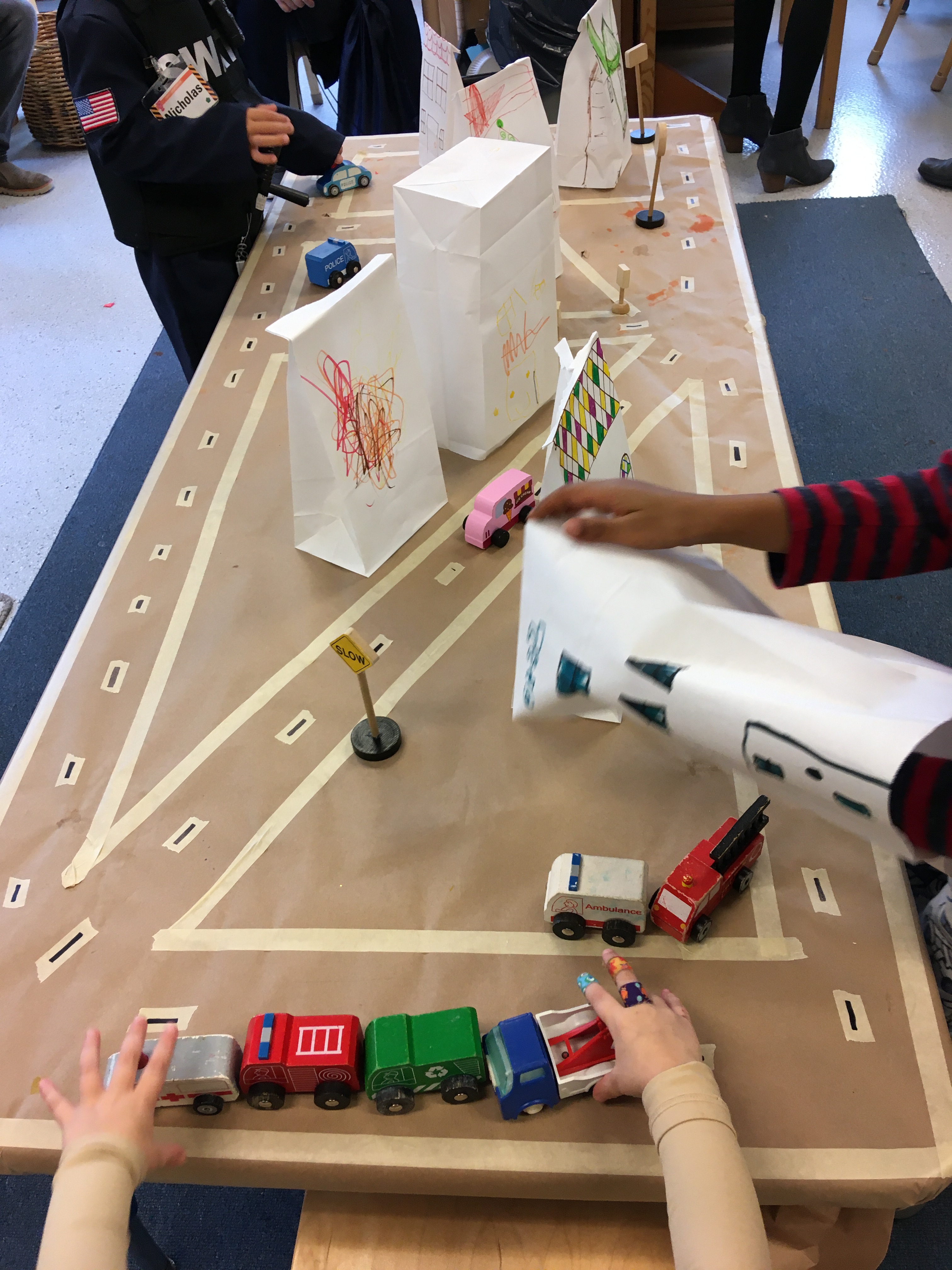

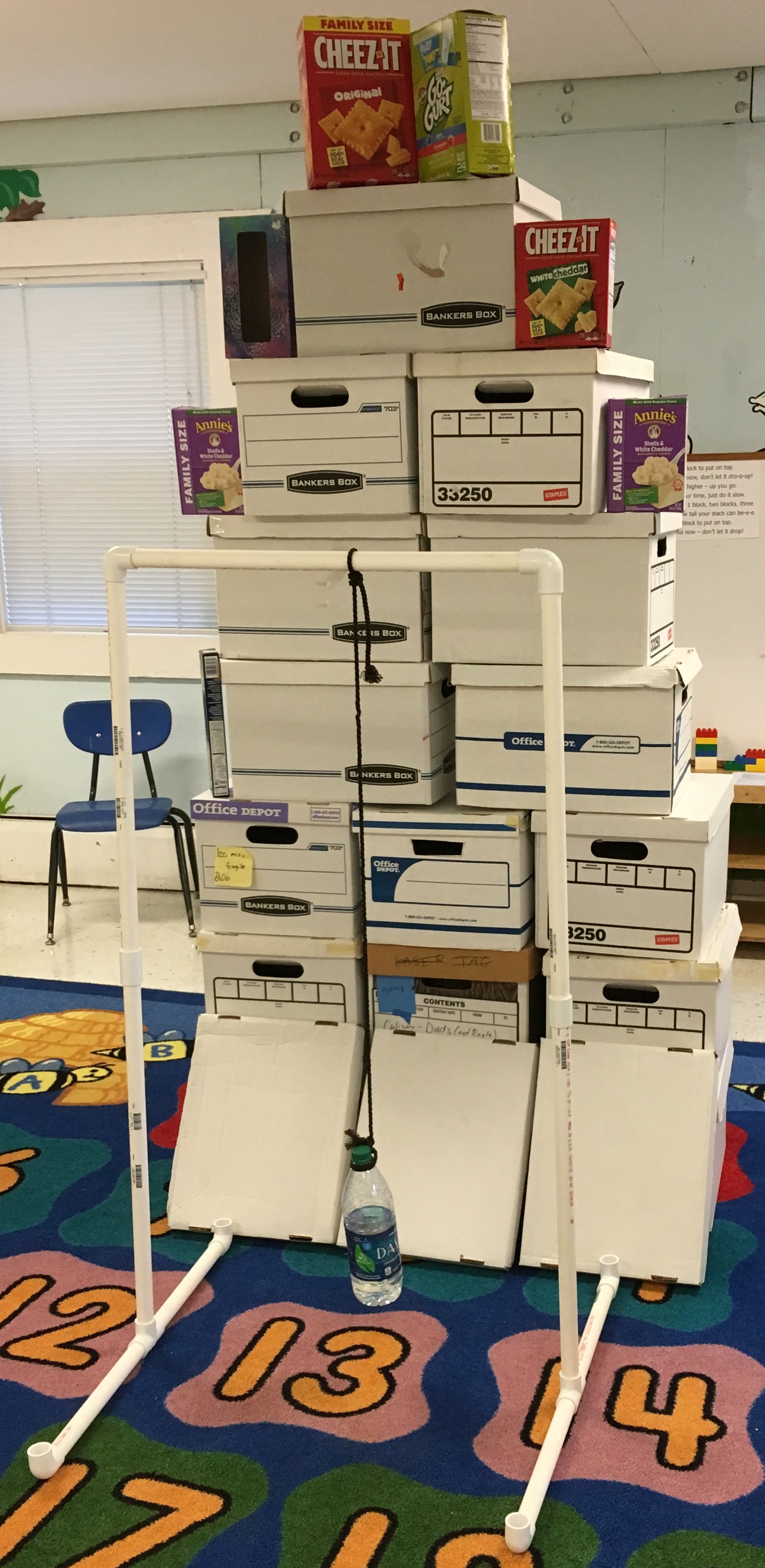

The Invitation to Play: the teachers may offer construction toys (like Legos, blocks, Magnatiles) or other creative building supplies (TP tubes, toothpicks and gum drops). Children are encouraged to use them to build any structure they choose. Teachers often mix in other supplies for inspiration: for example, add a toy giraffe and an elephant and children may build a zoo. Add cars and they’ll build roads and cities. Add pictures of famous buildings and they’ll build their representation of the Eiffel Tower. If one child wants to build a stable for her toy horses, and the other wants to make a spaceship, they have to negotiate how to share the blocks fairly.

When children build, they learn the basics of physics, spatial awareness, an understanding of what makes something stable. They learn about sizes and shapes and patterns – essential math skills. They problem solve and experience logical consequences that guide them in how to try again and build it better. They view themselves as competent creators.

Puzzles, shape sorters, manipulables

When a child puts a puzzle together or works with specially designed early learning materials, they learn important ideas about shapes, sizes, patterns, the relationship of the part to the whole, eye-hand coordination, small motor skills, and problem solving. However, many parents don’t buy many puzzles or pattern blocks, because they may be something a child just does a few times and masters. But at a preschool, they may have a whole cabinet full of spatial challenges for your child to explore.

Sensory Play and Play Dough

Sensory Play was once a staple of most preschools and many kindergartens. As public schools have shifted toward teaching academic skills that can be evaluated in standardized tests, sensory play is often phased out.

But when children play in a sandbox, or in a sensory bin full of rice or pompoms, or a water table, or on a light table, this multi-sensory experience can teach so many things. They build eye-hand coordination as they pour and scoop; learn concepts of empty and full, volume and weight – relevant to math; properties of solids and liquid in motion, that the amount of a substance remains the same even when the shape changes, and that some things sink and some things float (science!) They get comfortable with their hands being messy. (This is an important life skill – sometimes we all have to do messy things!)

In the sensory tables, and with play-dough, they can explore how to use so many tools: tweezers, tongs, spoons, scoops, shovels, funnels, rolling pins, cookie cutters, egg beaters and whisks, pipettes and eye droppers, scales, measuring cups and spoons, potato mashers, pizza cutters…

Playdough also gives children the opportunity to

- express feelings, squeezing and pounding

- learn about negative and positive space when they cut out shapes with a cookie cutter (this helps with reading)

- build finger muscles

Art Process / Writing Practice

Preschools often have an easel set up every day, with various kinds of paints and various kinds of painting tools – brushes, rollers, sprayers, or sponges. Children are free to paint anything that they choose to. Many preschools have a “creation station” for collage, offering cardboard and paper for bases, glue and tape, and miscellaneous things to glue on: pompoms, googly eyes, plastic lids, tissue paper scraps, styrofoam popcorn, pretend jewels… almost anything! Many preschools have a writing station with office supplies – paper, markers, pencils, pencil sharpeners, staplers, hole punches, scissors, stickers, rubber stamps, envelopes and so on. Children can make cards for their parents, signs to support their pretend play, booklets, anything they choose. We also do wacky things like salad spinner painting or painting with cars or putting a paper plate on a record player and drawing as it goes round and round.

These are all process-based art activities. No one is dictating what they must create there or what the final product needs to be. It’s completely up to the child to envision something and to make it real.

The children learn how to use all the tools and all the media, they build their finger muscles and their pencil holds, they learn names of colors and how to mix new colors, they learn to recognize shapes and to create shapes, they learn about symmetry, balance, and design. The art is a creative outlet for expressing their feelings and learning that their ideas have value.

Art Projects and Crafts

In addition to art process, we also have projects. These are activities where the teacher creates a sample and puts out all the materials for kids to make a project similar to the sample. It’s up to the child whether they want to use the materials in that way or do something else with them. But we do encourage them to try re-creating some projects, because it gives them practice with following multi-step directions. It lets them practice close observation skills and learn how to imitate or re-create what they see. We can build new skills into these projects they can then apply elsewhere, such as a project where they practice cutting curvy or zigzag lines.

Cars and Trains / Doll Houses / Play Farms

We have toy trains, toy cars, bulldozers and more. Children learn how wheeled vehicles move through the world and what happens when they crash. They learn how things need to be pushed up hills, but going downhill, they go fast on their own (physics!). And, because these toys tend to be very popular with our active, high energy kids, they also often provide opportunities to practice sharing and conflict resolution!

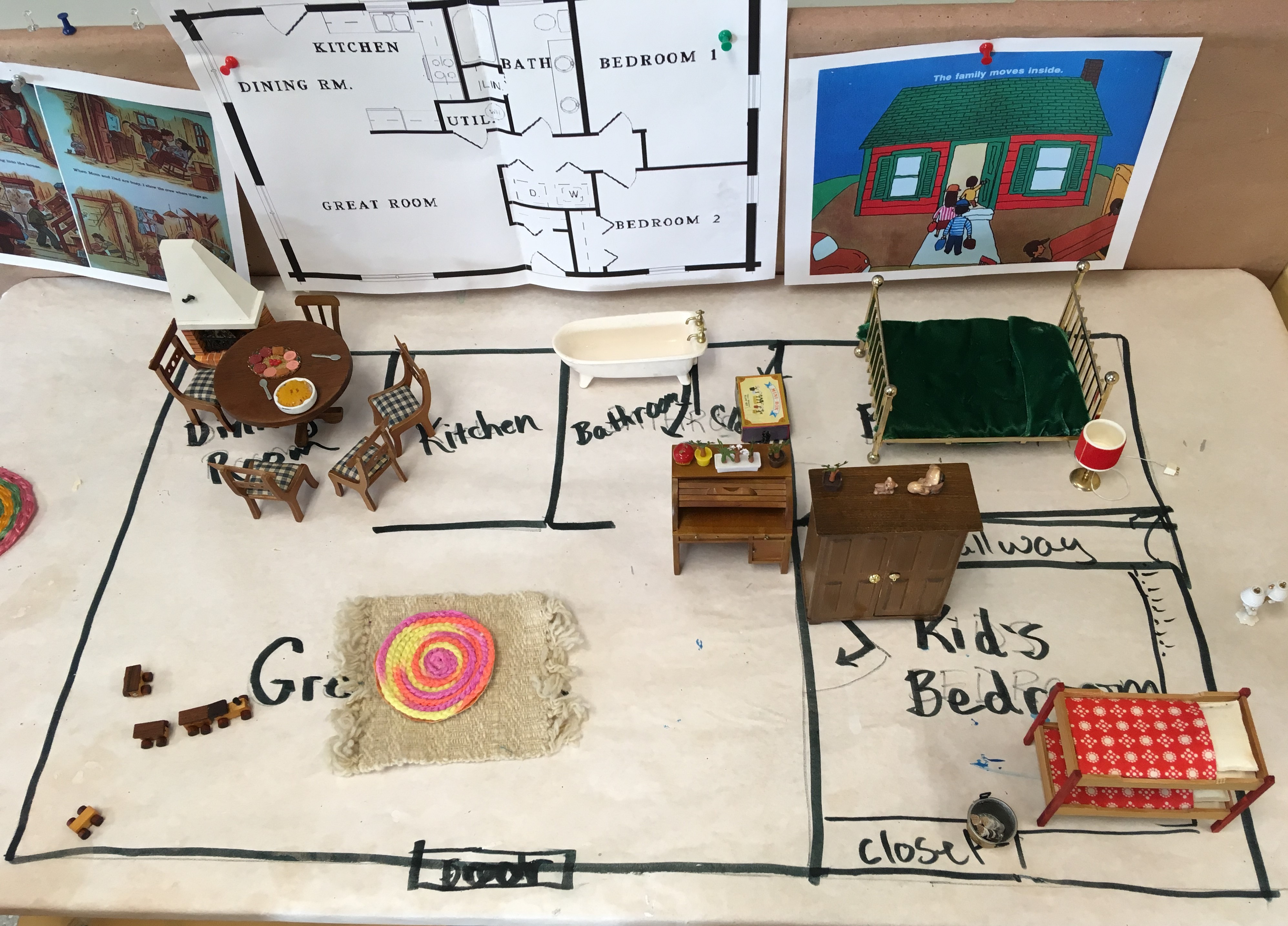

We have small dolls and doll house furniture. We have small plastic farm animals and farm equipment, woodland animals, and zoo animals. Kids may play with these and the cars on their own or they may be combined with the blocks, sensory bins, art supplies, pretend houses we made, and more. When children play with these small worlds, they do a lot of sorting (“I’ll put all the cows in this stall and all the horses in this stall”), counting (“I have 7 racecars that are ready for the race to begin”), and story-telling (“the lions were all roaring at the elephants”). They also co-create with other children – playing side by side sometimes, but then having their horse talk to the other horse, or their doll call the other’s doll to the table for food.

Dramatic Play

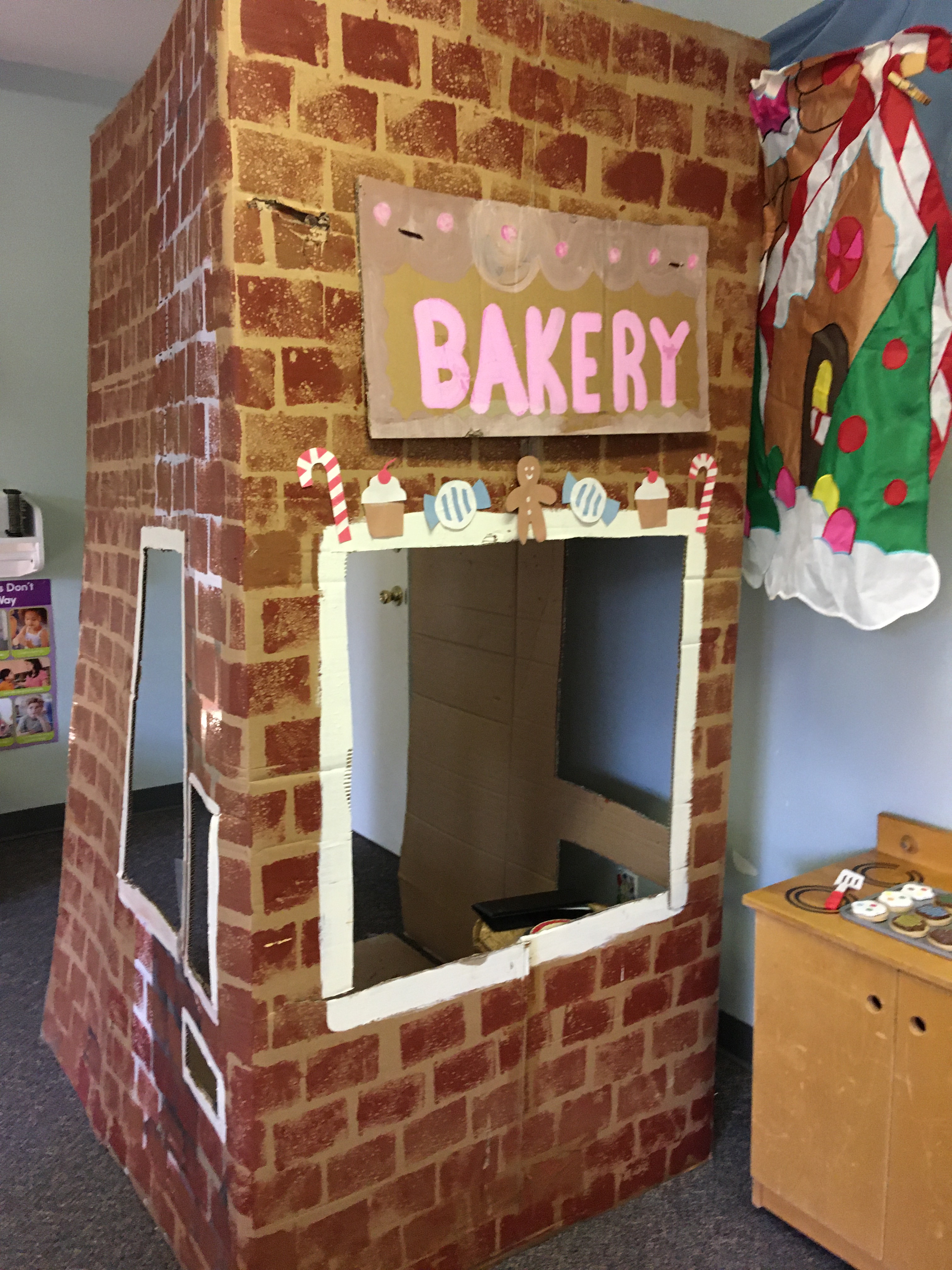

Most preschools have a play kitchen full of pretend food, dress-up clothes that allow children to play out many roles, plus baby dolls and stuffed animals to practice nurturing skills with. Many of those materials may be available every class during the year so children have lots of chances to explore them and use them in many ways. Teachers may also have special themes for dramatic play: maybe a farmer’s market in the fall, a gingerbread bakery in December, a valentine post office in February, or a spaceship and mission control.

With dramatic play, children learn to use their imagination, try on different roles, explore other cultures, imitate parenting behaviors they see in their lives, role play a variety of careers, and explore gender roles. Lots of complex language practice happens during pretend play. This area also builds social skills as they have to negotiate about which roles each child will play and what the story line will be.

Board Games and Active Games

Whether it’s Candyland, Bingo, Hide and Seek or Tag, all games offer practice at understanding and following rules, learning how we all get along better when we can agree to and follow the same rules, and learn how to be a good sport – winning with grace, and recovering from the disappointment of losing.

Books and Literacy

Stories are always available in a preschool classroom. Some schools (like Waldorf) use only oral storytelling, but in most, there are books available. They may be used during group time, but also available for independent exploration. Literacy practice may also be incorporated elsewhere: signs or menus in the pretend play area, books on CD to listen to, board games, and in art projects.

Children learn that letters on a page represent words – language written down, then learn to interpret pictures and to follow the development of ideas in the plot of a story. Most important, they see that learning to read is important and enjoyable.

Large Motor Activities / Outdoor Play

So much brain development happens in these early years, and children form the foundation of all the skills they need for a lifetime. This is especially true of motor skills. In addition to all the fine motor practice of puzzles, writing and playdough, preschools also offer lots of opportunity for large motor practice indoors and outdoors. Playing in the playground or on tumbling equipment indoors, throwing balls or throwing paper “snowballs”, digging in the sandbox or running on an ever-evolving obstacle course.

They are building physical strength, coordination and balance as they build all the key physical skills of running, jumping, climbing, and rolling. They learn to take some risks and be bold, while also learning when they need to be cautious, and learning to emotionally regulate through it all. There’s also important skills in taking turns on the slide, watching out for other people before moving, and moving around others carefully. As our kids ride trikes madly around the playground they’re learning skills they’ll need in driver’s ed someday!

Snack and Clean-Up Time

Snack time can always include practice at choosing and trying new foods, practice using silverware and table manners, learning to sit with others while eating, and practicing social conversation. Many preschools also involve the children in making their own simple snacks, which can include practice with cutting with a knife, stirring, spreading, sprinkling, measuring, and so on. Learning these life skills at an early age builds confidence and competence.

Children also learn confidence and competence as they help out with clean-up time. They may help put all the toys away, wipe tables, sweep the floor, put lids back on markers, and fold up the tumbling mats. This teaches life skills, teaches them that they can make meaningful contributions to a community, and motivates them not to make too much of a mess in the first place! But also, putting away toys is a great exercise in sorting things into categories (a key science skill) which requires noticing details, observing similarities and differences in object, concepts of color, size, and shape.

Check out the overview of play-based preschools.