TL/DR summary: Giving a child choices (e.g. what to wear, what story to read) can help to build a positive relationship where the child feels valued, empowered, and learns decision-making skills while having fewer power struggles. But if we offer too many choices, the child may feel overwhelmed and the parent may feel out of control. Finding the right balance starts with the parent deciding which options are available (setting limits), then the child choosing between those workable options.

My post on Offering Choices to Children covers the nitty gritty of how to use this discipline tool. This post is more of a philosophical think piece about the long-term impact of how we handle choices in our families. (Note: in this post, I talk a lot about parenting styles. Learn more about the Four Parenting Styles.)

Three Approaches to Offering Choices

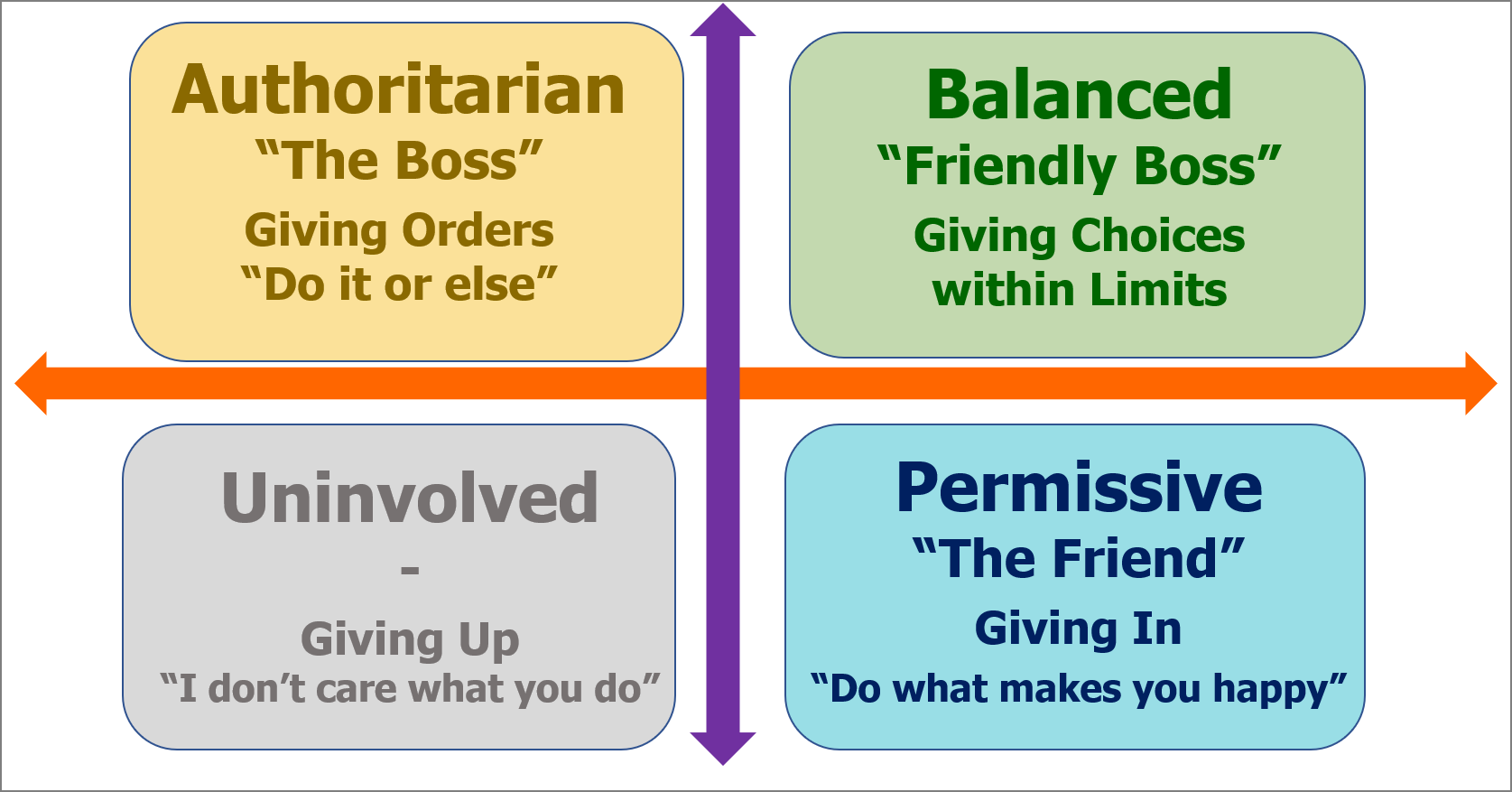

Several times each day in the life of a parent and a child, there are decisions to be made: what to eat at a meal, what to wear, what to do, which story to read, and on and on. Some parents, who learn toward the authoritarian style of parenting make almost all the choices, telling their child what the required plan is. Some parents who lean toward the permissive style let their children make all the choices. Let’s look at the possible pitfalls of taking either of these approaches to an extreme, then let’s look a more balanced (authoritative) approach.

Giving Orders – The Parent Makes All the Choices

There may be lots of reasons some parents want to make all the decisions. Sometimes it’s just that a parent wants to be in full control (“it’s my way or the highway”), sometimes it just feels faster and easier to make all the decisions rather than waiting on your kid to decide, sometimes it is an parent who has very high expectations for the child and believes they know the best route to achieving those. This has been called Tiger Mom parenting style, named after Amy Chua’s book, in which she describes her choices such as requiring that her children play piano and violin and requiring them to practice, saying “To get good at anything you have to work, and children on their own never want to work, which is why it is crucial to override their preferences… Once a child starts to excel at something… he or she gets praise, admiration and satisfaction. This builds confidence and makes the once not-fun activity fun.”

This parenting style can work well for some parents and for some kids.

But, it can also backfire in a few ways.

- Some children rebel against this – in the short term, that means lots of power struggles, and in the long-term it can damage the relationship with the parent.

- Some children feel dis-empowered and discouraged, or some feel that their parent doesn’t care about them.

- Children raised this way may not learn independent decision-making and initiative.

If you lean toward the more authoritarian style of parenting, it’s import to be aware of these potential pitfalls to help you to avoid them.

Giving In – Parents Let the Kids Make All the Decisions

This style of parenting could also be called permissive or laissez-faire. Dayna Martin, proponent of Radical Unschooling, says ““[This] includes trusting your child in what they choose to learn; you extend that same trust to other areas of your child’s life, like foods, media, television, bedtime. Parenting is supposed to be joyful, and it can be when we learn to connect with, rather than control, our children. The focus of our life is on happiness and pursuing our interests with reckless abandon together.”

Again, this can work well for some parent and for some kids. But, it can backfire.

- Sometimes children make bad choices, especially if they are given free rein and not much guidance. Like wearing a swimming suit in the winter or eating so much chocolate they get sick. Then parents have to decide whether to let the child live with the consequences of that bad choice – “guess you’ll be cold” – which can be fair or can be cruel depending on how far you take that, or whether to rescue the child from the consequences to keep them happy – which may mean they never learn from their mistakes.

- I have seen children who don’t do well in school or in peer relationships when they’ve been raised in a very permissive environment and don’t understand limits. The child who takes toys away from others any time she wants them and who eats all the cupcakes on the table will soon alienate their friends.

- Having to make choices all the time can actually be exhausting and overwhelming for kids. Being asked to make too many choices all the time can lead to meltdowns for little ones. Having choices within limitations can be very calming. Imagine being thirsty and walking into a convenience store in a foreign country where you don’t recognize any of the packaging, and you can’t figure out which of forty options to choose. Wouldn’t it be so much easier and more pleasant if someone said “I know you like juice – here’s the grape juice, the apple juice, and an apple cranberry juice – which one would you prefer?”

- Another common backfire for permissive parenting is that the parents may start feeling like they’re out of control. Some parents just end up feeling frazzled all the time, feeling powerless, and not able to see any way to change how things are going with their kids. Other parents, when they start feeling out of control will hit a certain high stress point, then suddenly flip-flop from permissive to strict – going from “you can do whatever you want” to “I’m done, you’re grounded for a month.” This inconsistency is extremely stressful for kids, and can lead to a lot more anxiety in the future over making their own decisions.

Giving Choices – The Balanced Approach

I believe that for most families the optimal approach is the authoritative parenting style. The parent has high expectations for the child and wants them to be successful, so they set clear limits and ensure the child is choosing between options that can be healthy for them (e.g. good nutrition, clothing appropriate to the weather, doing their homework, practicing their chosen sport or instrument). But the parent is also highly responsive to the individual child – ensuring that there are options that the child will enjoy and giving some flexibility for the circumstances of the moment.

Ellyn Satter, author of Child of Mine and How to Get Your Kid to Eat: But Not Too Muchhas some important ideas about the division of responsibility in feeding. The parent is responsible for what, when, and where the child eats. The child is responsible for whether to eat, and how much. The parent puts healthy options on the table, the child makes the decision from there, and the parent can relax, knowing that any choices the child makes can work out OK.

I think a similar approach could apply to almost all decisions, from getting dressed, to choosing a bedtime story, to choosing extracurricular activities to choosing where to go to college and what to major in. The parent first evaluates the possible range of options, and decides what criteria would represent a good option. If they’re working with a young child, the parent might and offer only a limited number of viable options (2 options for a 2 year old, 3 for a 3 year old… “do you want the blue shirt or the red one?”) For an older child, they might say “you can choose amongst any of these options, but here’s our limitations and here’s our criteria. You can only choose things that fit those requirements.” (“It’s cold out today, so choose something warm to wear.”) The parents are the ones “setting the table” with options. The child then is empowered to make the choices within those limits.

I have always told my children “you may be as smart or smarter than I am, but I am wiser than you and will always be wiser than you because wisdom comes from life experience and seeing all the long-term impacts of choices.” So, when I tell them the criteria for a positive choice, that’s coming from all my wisdom. When I let them make the choice, I acknowledge their intelligence and give them decision-making practice for their future.

It’s worth acknowledging that authoritative parenting requires more effort from the parent than authoritarian or permissive parenting does. The authoritarian parent just has to say: here’s the rule – follow it or expect consequences. The permissive parent says: do what you want. The authoritative parent has to say: Here are the options, here’s information on the impact of your choices, let’s talk through how to make the best choice. It’s more work in the short term, but hopefully in the long term yields a child who is capable of making better decisions on their own.