The TL; DR summary – If you are hoping to encourage those around you to take more steps to prevent the spread of coronavirus: don’t shame them, do listen with empathy to their concerns, support their efforts at risk reduction, understand that people may make different trade-offs than you would, be intentional about who you interact with, help give other people the tools to have conversations about risk reduction, and model the behavior you would like to see.

Where do we start?

As a parent and a parent educator, I talk a lot to other parents. Many are angry when they see people not wearing masks – they may think “because of people like you, my kid can’t go to school!” They may shake their heads in dismay when they see unmasked teens hanging out in close-knit huddles, inches apart, saying “if that were my kid….”. They express frustration at in-laws who talk about having a lovely time at a party with friends (unmasked) and then want the grandkids to come to their house for a visit. They read social media posts from friends who believe coronavirus is a left-wing conspiracy, and ask me: do you sometimes feel like you want to shake people and say “what the h*%$ is wrong with you?”

But let’s be honest: Do you think that scolding anyone for the choices they make will make them change their ways? No. You know that will just make them dig in their heels more. But what approaches might work to encourage more people to take more steps to prevent coronavirus spread?

We can learn a lot from previous approaches to public health messaging, and approaches to education in general.

Shaming Doesn’t Work

Julia Marcus, an epidemiologist and professor at Harvard Medical School, has been doing some great writing and interviews on this subject. (In The Atlantic, Teen Vogue, and the Harvard Health Blog.) Many of the ideas in this post come from her.

She talks about what we learned from AIDS: “When you shame people as a way to try to get them to avoid risky health behaviors, it doesn’t generally make the behaviors stop — it just makes people want to hide the behaviors…” It’s hard to hide not wearing a mask, so some people may decide to have indoor parties with friends, and then later won’t disclose that to contract tracers. “So rather than shaming, what we can do is try to meet people where they are, understand what is getting in the way of them adopting the protective health behaviors that we want to support, and then try to mitigate those barriers.” (Source)

I teach about positive discipline techniques – when we’re connected to someone, how do we shape their behavior. Although shaming someone doesn’t tend to be effective in the long run, the attention principle does. Pay attention to whatever behavior (no matter how small) that you want to see more of. I have family in Kansas that worries that few people are wearing masks although they do put one on when they talk to her – just saying “I appreciate you brought your mask today” or “what a lovely mask” will do more to encourage them to wear it than saying “why aren’t you wearing it all the time?” Another idea from parenting / education that I find helpful is Ross Greene’s idea of “people do well if they can” – if they’re not doing well, what skills, tools, or support do they need to do better? This post will cover lots of those ideas.

Try Empathy

If you try to start a conversation by sharing all the information you have on why they SHOULD wear a mask, they can get defensive and push back harder. Or if they tell you about a party they went to, and you pull out your data sets, they’ll walk away.

“Instead of telling someone what to do right away, you want to explore why they’re doing it, and what is the reasoning behind their behaviors, in a very unbiased and nonjudgmental way,” says Dr. Michael Richardson. (Source)

70% of Americans believe people should wear masks. (Source) “But just like the well-intended condom on the nightstand that never makes it out of its wrapper, some masks don’t make it onto someone’s face—often for relatable reasons.” (source)

In one neighborhood in Seattle, here’s what people report about their actual behavior. Always wear a mask – 67%; Frequently – 18%, Sometimes – 9%. Rarely – 1%. Never wear a mask: 5%.

So, try asking people what their reasons are – what are their barriers?

Empathize with their experience. Listen to their concerns. Share your own frustrations, and the solutions you have found that work for you, being careful to make I statements not you commands. “I know – I hate how they fog up my glasses! I’ve had better luck with my new mask with the wire, but it is frustrating.” “I know, it’s weird to me to not see people smiling at me and not be able to smile back. I’m trying to figure out body language ways to communicate, like waving or nodding.” “I’m also so overwhelmed by the news that part of me wants to think this is a conspiracy and it can’t really be as bad as they say. But I still wear my mask, because what if I did have it and went out before symptoms developed, and someone I love gets sick because of me.” “I get so hot in the grocery store – I hurry along, reminding myself that the sooner I’m done in the store, the sooner I can get to my car and take my mask off.”

“Acknowledging what people dislike about a public-health strategy enables a connection with them rather than alienating them further. And when the barriers are understood, they become addressable.” (Source)

Risk Reduction Approach

It’s hard for all of us to abstain from social contact. It may be especially hard for young people and extroverts of all ages. Instead of demanding that they abstain from seeing their friends, maybe we need to take lessons from what we’ve learned in a comprehensive review of abstinence only sex education: “Many adolescents who intend to be abstinent fail to do so, and when abstainers do initiate intercourse, many fail to use condoms and contraception to protect themselves.”

“Comprehensive risk reduction (CRR) interventions promote behaviors that prevent or reduce the risks… These interventions may: Suggest a hierarchy of recommended behaviors that identifies abstinence as the best, or preferred method but also provides information about sexual risk reduction strategies.” (Source)

Instead of just talking about what someone can’t do, we could talk about what they can do and how to make that as safe as possible. Instead of saying “you can’t see your friends”, you start with “I get that you want to see your friends.”

Then, we can acknowledge that, from the coronavirus perspective, the safest option is just to stay home and talk on Zoom. But, if they feel they need to see people: then, talk about how to do that with less risk: such as using masks, social distancing, where to do that: meeting people outside, going for walks outdoors with someone, what to do – a bring your own picnic where you sit several feet apart; when to do it (when you’ve had minimal exposures recently) and who to do it with.

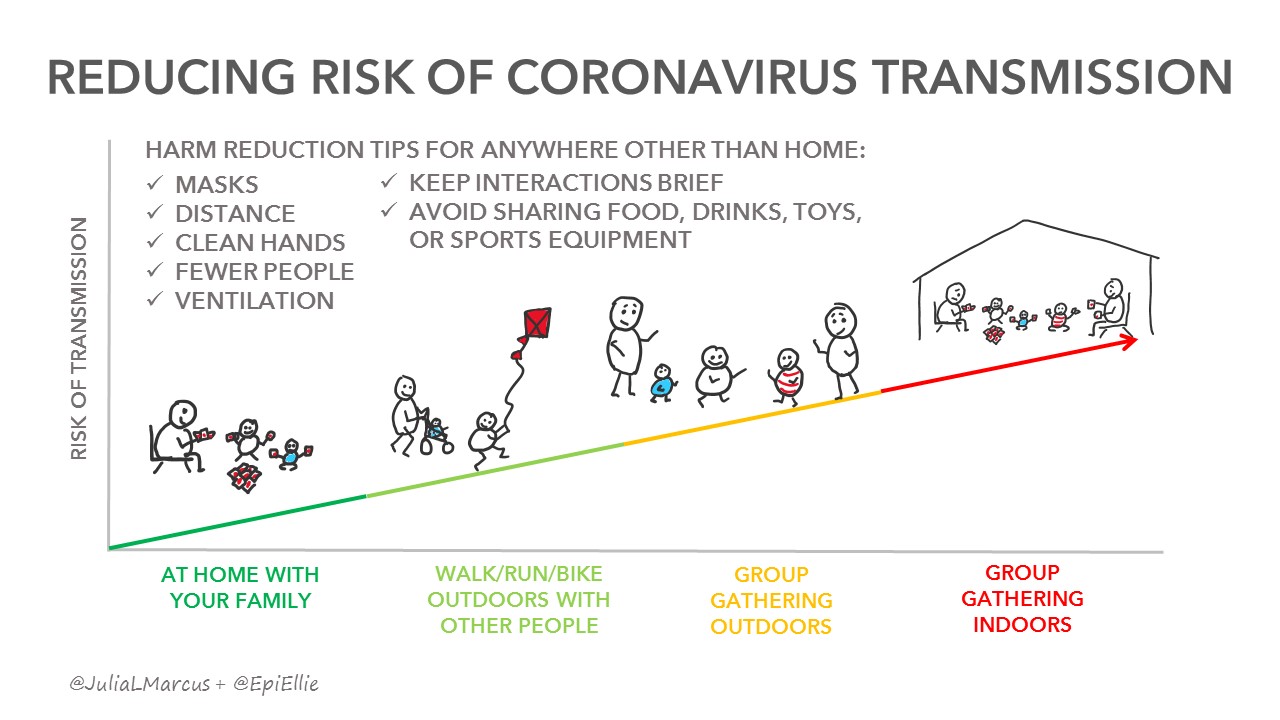

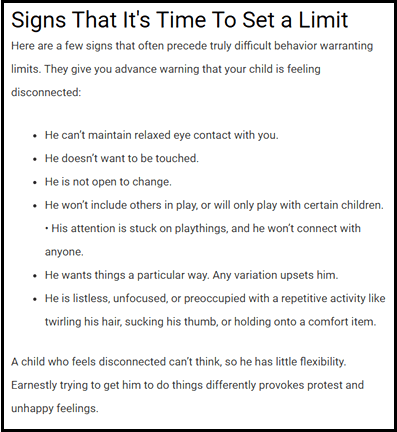

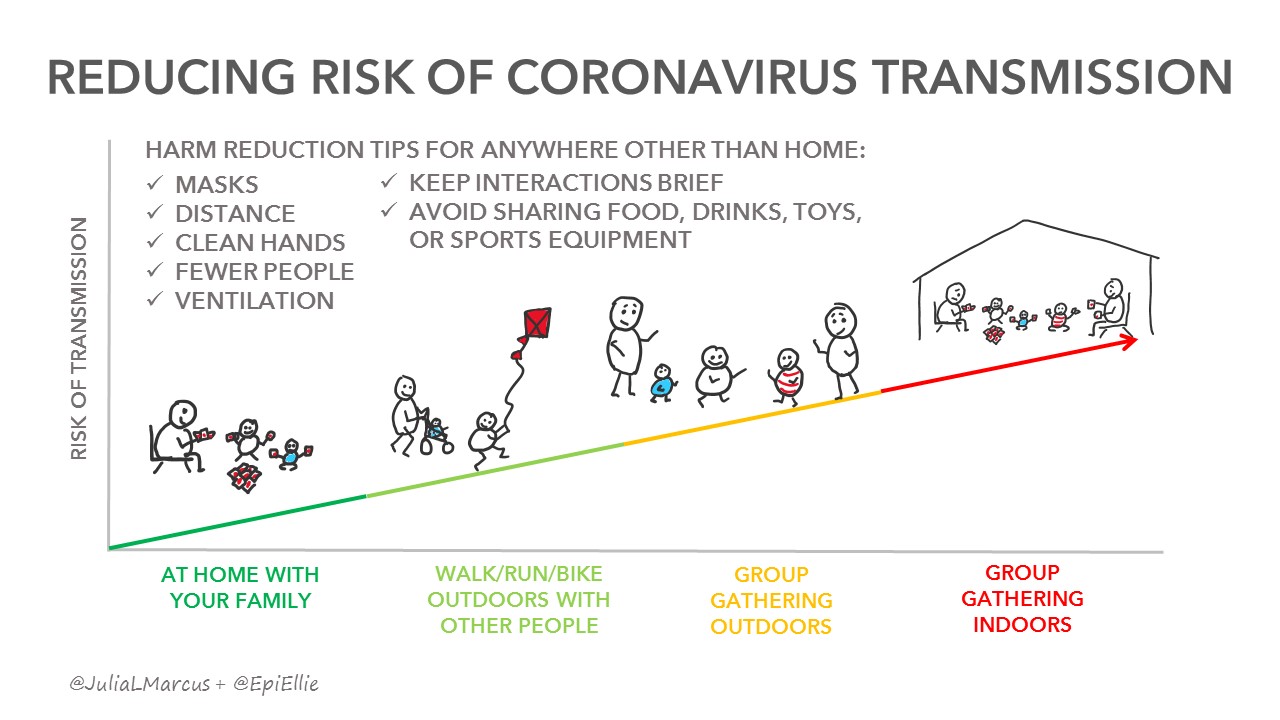

As Mark Levine, chair of the NYC Health Council, says: “If we don’t give people the information to choose low-risk activities, they will choose high-risk ones–like house parties, large gatherings in front of bars… So let’s give people the tools to understand that risk is a spectrum. * Outdoors is less risky than indoors. * Small groups are less risky than large groups. * Simply passing by someone is less risky than sustained contact.” He shared this graphic, which shows staying home with your children has the least coronavirus risk, then going out in the community, then meeting friends outside, and then playdates at a friend’s house, which you might only want to do after very careful consideration.

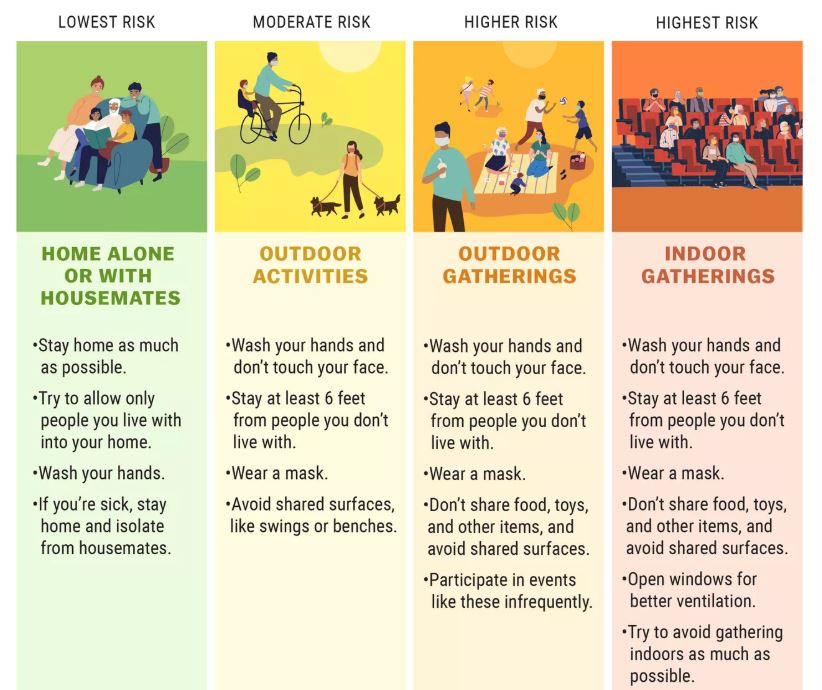

Vox took this idea and adapted it. Helping people understand the different levels of risk and what precautions need to be taken at each level can help them make decisions about the risk reduction methods they think they can follow reliably.

Trade-Offs

When we see teens and young adults hanging out at the park with friends, it’s easy to think they’re foolish and careless: “Young partygoers have become the latest scapegoat for America’s pandemic woes… Risk taking typically peaks during young adulthood, when people are most responsive to the rewards of a risky choice.” However, that may not be the whole story: “The issue isn’t that young people are universally unconcerned about the pandemic; it’s that they realize it’s not the only—or even the greatest—risk they face… [young people are at] lower risk of complications from coronavirus infection than older people—but at far greater risk of psychiatric disorders that can be triggered or worsened by social isolation…” (Source)

For sake of reducing coronavirus risk, the safest thing would be for all of us to stay at home. However, many of us can’t, due to work or other requirements, or lack of a safe home environment. And there are many other reasons we might not want to stay at home. How do we balance the demands and desires to get out of the house with reducing risk of transmission?

I’ve worked with pregnant clients for over 20 years now. When I talk about healthy nutrition, avoiding substances and medications and so on, I have always tried to take the approach of offering the best information we have about what is best for a developing baby, while also acknowledging that babies are surprisingly resilient. I encourage making the healthiest choices, but also say – “if you’re making an unhealthy choice in one area, can you try extra hard in the other areas to balance it out?”

If I tell a smoker about all the evils of smoking and that they should never ever smoke, they might rebel against that – “my friends all smoke and their babies are fine!”, or they might give up – thinking – if I can’t do anything right, why try at all. Instead, I say “we know smoking is harmful, so it’s best to avoid it or reduce it as much as you can – in the meantime, here are some other healthy choices you can focus on.” And typically, they make these other healthy choices and significantly reduce their tobacco use.

We can take some of the same approaches to coronavirus. Balance the risky choices with low risk choices.

We have mostly had our son at home for 4 months now. He’s barely been in other buildings or with other kids. But, next week, he’ll go to an in-person summer camp. We’ve decided that he needs that brief respite from quarantine life at home and that brief chance to engage with other kids and build his social skills (our son is autistic, so this is especially challenging for him). But, in making that decision, we also looked at risk reduction – making sure the camp had good protocols, and at other trade-offs. This week we’ve had minimal contacts to ensure he’s healthy and not bringing something to camp that will affect others, and for ten days after camp, we will be extra careful not to expose others to him (or us) just in case he picks something up. And of course, there will be masks and lots of hand-washing.

So, different people may have different degrees of comfort with exposure risks and how they’re managing them. But each of us can be making our own decisions, and figuring out our own trade-offs.

“Instead of moralizing, harm reduction comes from a place of pragmatism and compassion. It accepts that compromises will happen— for perfectly understandable reasons—and aims to reduce any associated harms as much as possible.” (source)

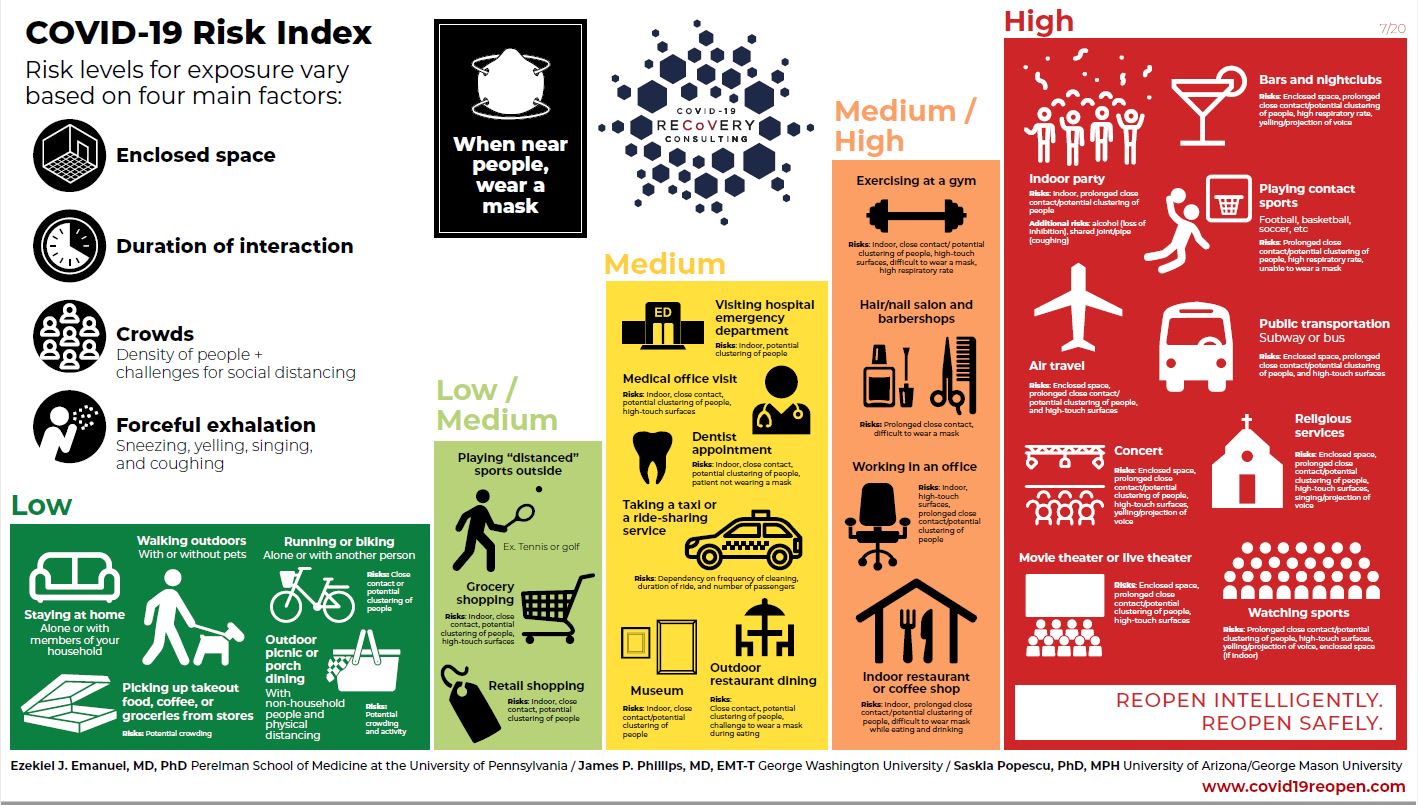

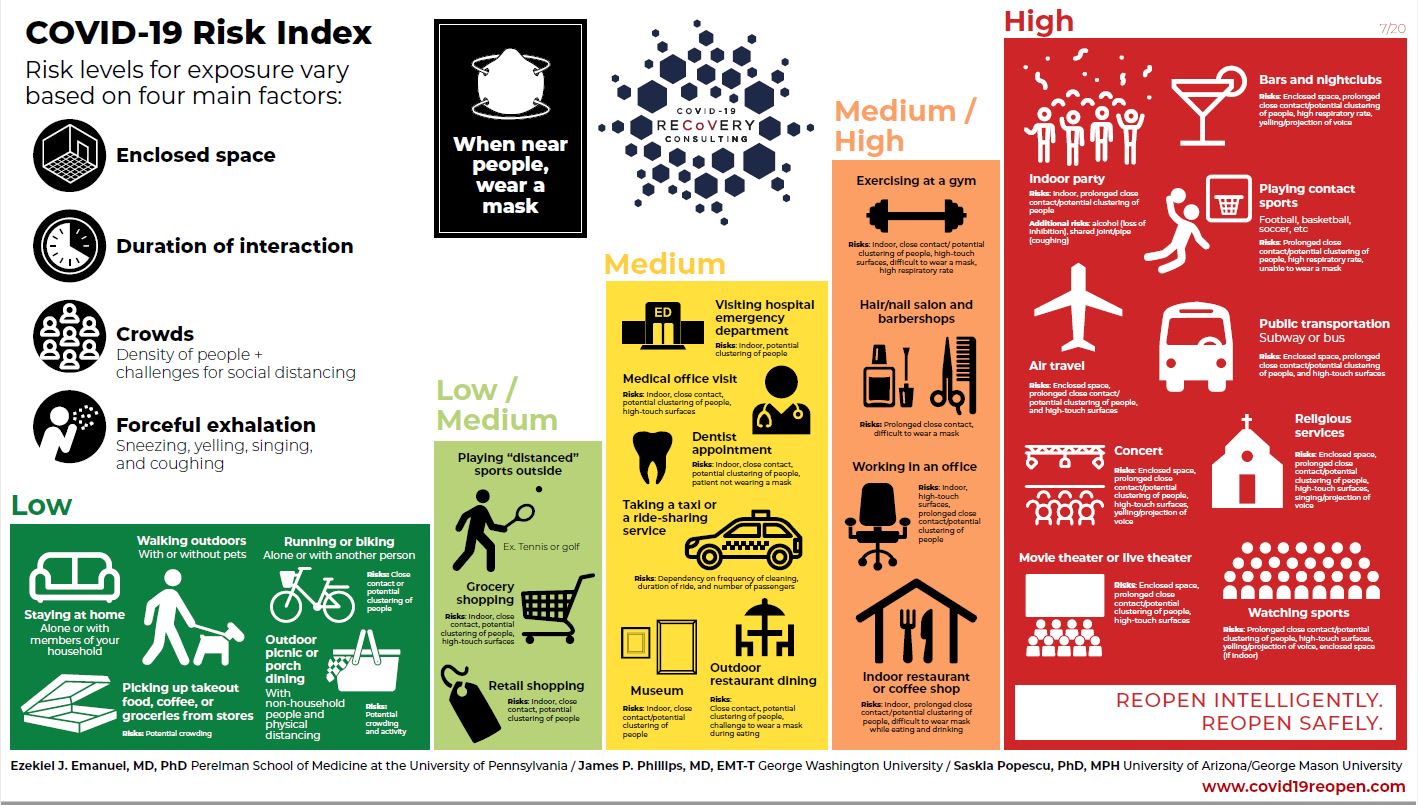

It helps to have a tool for comparing risks. I really appreciate this risk index infographic from Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, Dr. Saskia Popescu, and Dr. James P. Phillips, which looks at the risk of various activities, assessing based on 4 factors that increase risk of transmission: Enclosed space, longer duration of interactions, crowds, and forceful exhalation (e.g. singing, shouting, breathing fast while exercising.)

Bubbles and Pods

Many people have chosen to “expand their bubbles” or “create a pod” where a small number of people choose to socialize exclusively with each other as a “quaranteam” without the need for physical distancing. I know of many parents of young children who have made this choice so their kids get a chance to practice and develop social skills (and so the parents get an occasional break from 24/7 child care.) Check out this article on the Dos and Don’ts of Quarantine Pods and CNN’s Guide to Creating a Pandemic Bubble. This article in Slate does a nice job of talking through one person’s experience with this. The point of a pod is to be intentional – rather than having random encounters, you really think through what type of contact you most need, and with whom, and be sure that the people in your pod have a similar risk tolerance and exposure level to you.

Navigate Social Barriers

Bubbles require a lot of awkward conversations and negotiations. When gathering with others, it can be hard to be the one to start the conversation about how to reduce the risk of gathering. Some people, especially teens and younger adults, may find themselves going along with risky behavior because they don’t want to be seen as the wimpy, over-cautious person. They may need somewhere to practice limit setting. We learned with the “Just Say No” approach to substance abuse education that it wasn’t enough.

Just Say No was “essentially a failure at dissuading young people from doing drugs. … teenagers enrolled in the program were just as likely to use drugs as those who did not receive this training. Programs that did make a difference acknowledged the difficulty of just saying no, coaching kids on how to handle social expectation and peer pressure.” (Source)

“[Effective programs] teach students the social skills they need to refuse drugs and give them opportunities to practice these skills with other students — for example, by asking students to play roles on both sides of a conversation about drugs, while instructors coach them about what to say and do. [They] take into account the importance of behavioral norms: they emphasize to students that substance use is not especially common and thereby attempt to counteract the misconception that abstaining from drugs makes a person an oddball.” (Source)

Starting to have conversations about reducing coronavirus risk while still interacting with others can help reduce the overall risks.

Role Modeling

Sometimes the most effective way to make change is to be the change you want to see.

If parents want their kids to wear bike helmets, they should too. If one tween in a group puts on a bike helmet, the others will too.

We started wearing masks to the grocery store before it became common, and once I noticed that someone we passed by then took her mask out of her purse and put it on. She wasn’t quite bold enough to be the “only one” but seeing other people make that choice made it more comfortable for her.

I have also found that if I can talk about my decision-making in a calm, reasoned way, rather than with fear-mongering and scolding, it can create more openness in others for making their own thought-out decisions rather than knee-jerk reactions.

“Unlike abstinence-only messaging, which simply instructs people to stay home, a harm-reduction approach acknowledges that people will take risks for a variety of reasons, including a basic need for pleasure….The abstinence-only and harm-reduction approaches share the same goal of reducing the cumulative burden of severe illness and death. But harm reduction is more likely to achieve that goal by supporting lower-risk—but not zero-risk—activities that can be sustained over time.” (Source)

Vox has a very helpful collection of coronavirus risk reduction tips: 8 ways to go out and stay safe.

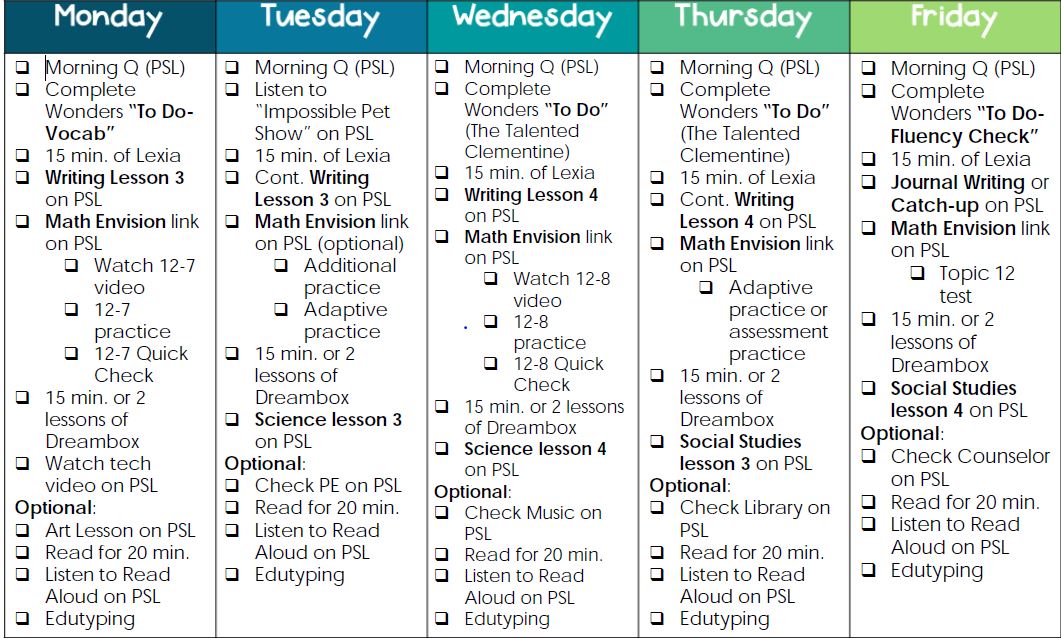

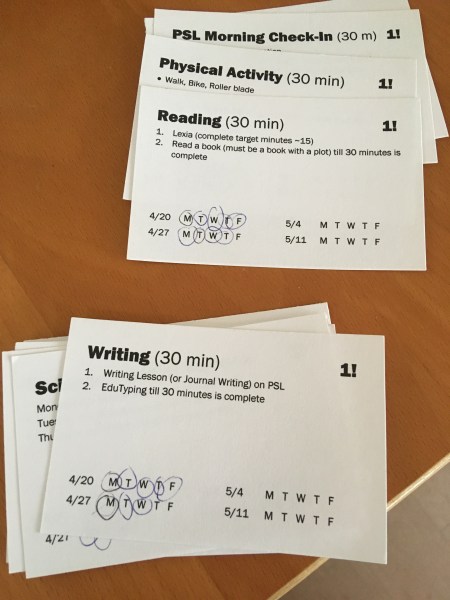

We have a system of cards, each representing a piece of his work. He has to complete 8 cards a day. When he has completed 4, he earns an hour of screen time. When he has completed 8, he earns a second hour of screen time. Then, he is done with his work for the day, and done with screens for the day. Each day he has 6 cards that are required (morning check-in, reading, math, writing, science/social studies, and physical activity – he needs to burn off some energy for all our sanity!) The others are flexible – practicing playing recorder, calling his grandparents, helping with extra chores, etc. Click here to see all his:

We have a system of cards, each representing a piece of his work. He has to complete 8 cards a day. When he has completed 4, he earns an hour of screen time. When he has completed 8, he earns a second hour of screen time. Then, he is done with his work for the day, and done with screens for the day. Each day he has 6 cards that are required (morning check-in, reading, math, writing, science/social studies, and physical activity – he needs to burn off some energy for all our sanity!) The others are flexible – practicing playing recorder, calling his grandparents, helping with extra chores, etc. Click here to see all his: