Time Out is an important tool in the discipline toolbox, but it’s an easy one to mis-use or over-use, and it doesn’t work for all families, but let’s examine the best practices for time out.

(* Age note: For a two year old, we don’t really do a prolonged Time Out with this full method. We would instead: remove the child from the situation, hold them calmly for a minute or so, or sit with them till they’re calm, then let them return to play. )

What is Time Out?

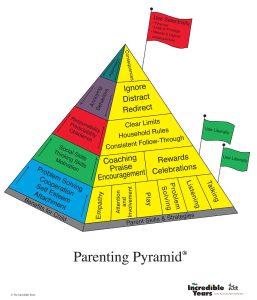

First, let’s understand what it is: It’s Time Out from Positive Attention. Children like attention, so will act in the ways that get the most notice from their parents – whether it’s negative or positive attention. So, for mild misbehavior that’s just annoying, we use the “Ignoring” tool. For bigger issues, we use Time Out, which is spending time in a boring place, for a prescribed time, getting no attention. Time Out is a chance for your child to calm down (and for you to calm down), then return to better behavior. Time Out is not jail… it’s not intended to make your child suffer for their crimes.

Time Out will only be effective within the context of a supportive, loving relationship. If your child normally gets lots of positive attention from you, then Time Out is a big change from that. If your child is often ignored, Time Out isn’t much different, or the process of misbehaving and being sent to Time Out may be the way the child actually gets themselves some attention from the parent.

Developing Your Time Out Plan

Make your plan in advance for how you’ll use time out. (Springing the idea on an unsuspecting child in the middle of a meltdown is not going to work!)

Explain your plan to your child in advance, when everyone is calm. Practice it a few times at a family meeting so everyone knows exactly how it will work, and what the goals are of using it. Make sure your child clearly knows what behavior will lead to a time out.

When: What Behaviors Lead to Time Out

Time Out is best when used sparingly, for aggression – situations when your child is hurting someone or something, or for non-compliance – times when you have tried other discipline tools and your child continues to disobey. (Note: all young children ignore or disobey about 1 out of 3 commands. If a simple reminder gets them to comply, you won’t need Time Out – it is for more intentional or chronic non-compliance.)

Sometimes, you may want to send your child to a Time Out because you need a break. That’s not a fair use of Time Out. If you need a break, be honest about that, and take one. Do this before you explode…

Where:

Select a place for Time Out. It should be:

- Boring: Somewhere with no toys, books or screens to provide pleasant experiences.

- Out of the way of the flow of traffic, so you don’t have to move past the child, and not in a place that tends to draw the attention of other children. (For example, the back of the classroom is better than the front, or just around the corner from the dining table where you can keep an eye on them but your other children can’t see them, is better than somewhere that will draw the attention of other kids (who then may try to provoke the child who is in Time Out.)

- Safe: Bathrooms or kitchens can be dangerous places for kids to be without close supervision.

- Some parents avoid the child’s bedroom as they don’t want the child to think of their room as a punitive place. Other parents, who focus more on the calm-down aspect of Time Out than the punitive aspect, may find that the bedroom works well.

- You might choose to include a few calm down tools in this place, such as a Calm Down Bottle, a favorite stuffed animal, a stress ball, a weighted vest or blanket, or bubbles to blow.

Call this the Time Out Place or the Calming Place. It’s not “the naughty chair.”

If your child misbehaves in public, consider using another discipline tool. If Time Out makes the most sense, you can go to your car, or to a quiet corner with them while they take a Time Out from your attention.

How Long

For a three year old*, we set a baseline of three minutes, for a four year old four minutes. For older children, we start at 5 but increase up to 9 if needed. (See below.) Longer Time Outs are not effective and may just make the child resentful and resistant to future Time Outs.

When they’ve reached the minimum time requirement and they’ve had a calm voice and body for a couple minutes, then you can declare that Time Out is over. (They don’t decide… you do.)

Note: the first couple times you use Time Out, it may take them longer to calm down. (Even as long as 20 minutes.) In the long term, we want Time Out to be as brief as possible for them to calm down and return. We want to help them realize that if they can calm down right away, then they’ll get out of Time Out as soon as the time requirement is met.

What and How

- Describe the problem behavior clearly. State what behavior you would like to see.

- Warn that if the problem behavior continues, there will be a time out. (If you’re not willing to do a Time Out right now, then don’t threaten to do one… Empty threats make it less likely the tool will work in the future.)

- Give a clear command, including the reason. Keep it short and simple. “You did ___. Go to Time Out now.”

- What they should do in Time Out: The goal is that they learn to calm themselves down. They won’t initially know how to do that! Self-calming skills are something we need to be teaching at other times when they’re calm so they may be able to use them in Time Out eventually. At first, expect that they will stomp, kick, yell and whine a lot in Time Out. Over time, they will learn that this behavior doesn’t gain them anything, and they’ll give up on it.

- What you do when they’re in Time Out: Give them as little attention as possible. Try to move on with your day, not nagging them, responding to their pleas, and so on. If they yell, don’t yell back. If they ask “how many more minutes” you don’t have to respond. (You could choose to announce when a minute has passed.) You might need to use your own self-calming skills and positive self-talk at this time to stay calm.

- If there are other children with you, encourage them to “use their Ignoring Muscles” and tune out the person who is in Time Out. You can continue to play nicely with the other child(ren), giving positive attention to their positive behavior.

- Once the time requirement has been met, if the child has been calm for two minutes, release them. If not, simply use a When/Then statement. “Please work on calming yourself down. When you have been calm for two minutes, then you can come out of Time Out.”

- When time out is done, re-engage with your child, and praise their first positive behavior.

What if they resist?

- What if they resist going to Time Out? If they are 3 – 6 years old, you say “You can go to Time Out on your own or I can take you there.” If they don’t go, calmly take them there. For a 6 – 10 year old, you say “I’m going to add an extra minute in Time Out. That’s 6 minutes.” Wait ten seconds. If they still don’t go, add another minute, up to 9. After that, add a consequence: “That’s 10 minutes now, and if you don’t go to Time Out right now, you will lose screen time privileges for tonight.” If they go to Time Out, after 10 minutes they’re done. If they won’t go to Time Out, we drop the power struggle over Time Out and they receive the consequence instead.

- What if they try to escape Time Out? You re-set the Time Out clock, and you say “If you come out again, then you will have this consequence.”

Using Time Out

It is best to develop a specific routine for Time Out, so you can do it the same way every time. Here are two sample scripts, based on the Incredible Years program:

Time Out for Aggression

“You hit. You need to go to Time Out.” Child goes to Time Out. Once time is up, and they have been calm for two minutes: “Your Time Out is Finished. You can play now.” As soon as you see any positive behavior, praise it – you’re returning positive attention to them.

Time Out for Non Compliance

This would be used for an on-going behavior challenge – such as when they’ve been resisting bedtime or doing chores or turning off the screen.

First, give a transition statement that tells them when you’ll be asking for a behavior and what you’ll ask for. “In five minutes, [your screen time will be over and you will need to calmly hand me the tablet].” Then, when the time comes, state a brief command. “Your time is up. Hand me the tablet now.” Wait 5 – 10 seconds for them to process the command. If they comply, praise and move on. If not, give an if/then warning about Time Out: “If you do not hand it to me now, then I’ll take it and you’ll have a time out.” Wait 5 – 10 seconds… if they don’t comply: “You didn’t give it to me. I am taking it. Go to Time Out.” If they refuse to go, or won’t stay in Time Out, warn of a consequence: “If you don’t go/stay in Time Out, then you will lose half your screen time for tomorrow.” After the Time Out is over and/or the consequence is imposed, then, if needed, return to the original command. (If this all started when you asked them to clean up and they refused to clean up, you can’t let that go… they still need to clean up. Otherwise, many kids would choose the 5 minute Time Out to avoid cleaning up!

Initial Resistance

Expect that the first few times you use Time Out there will be a lot of drama – they may resist, they may cry, they may throw things. After things are calm again, have another family meeting talking about what Time Out is, why you’re using it, and how it can be an easy solution if done well. Let them know that you will continue using it, and they can decide whether to make it a miserable experience for themselves, or whether to use it as a brief 5 minute calm down interlude that you can all move on quickly from.

Moving On From Time Out

Once time out is over, move on, don’t rehash. We all make mistakes, and need to come back in and try again. Don’t nag at them, let this be a clean slate moment. Give them positive attention and praise any positive behavior you see.

Important note: If they were using Time Out to get away from doing a chore, make sure they complete that chore after Time Out. Be matter of fact about this, giving positive feedback as they return to the work.

What Else Can You Do?

If you find yourself using Time Out every day, consider using other discipline methods for some of these situations. Choose a very limited set of behaviors that you will use Time Out for.

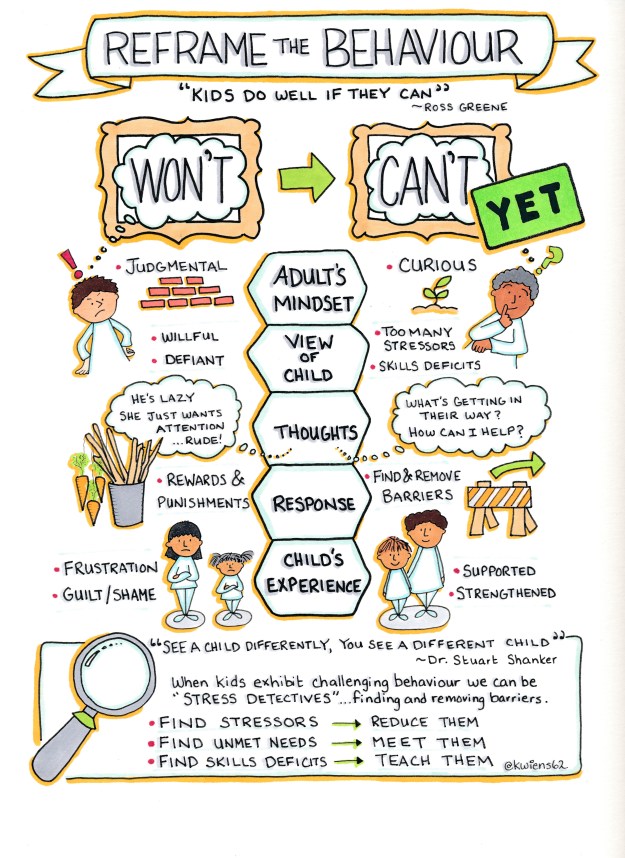

If you have been using Time Out for the same behavior repeatedly for multiple weeks, you need to form another strategy since it is not effectively changing behavior. (One thing to consider is whether or not your rules and expectation are developmentally appropriate for the child. Are you asking more of them than they’re capable of?) Seek help from a parent educator, teacher, or counselor if you need outside perspective to come up with new ideas.

Continue to teach other skills

Time Out does not teach your child what to do better. It can’t be used as your only discipline tool. Be sure to also be using positive attention, praise, guidance in what TO DO, teaching ways to understand and manage their big emotions, role modeling, and more to help your child learn how to behave better. When they’re mis-behaving, ask yourself whether consequences might be a better response than Time Out. Your long-term goal is self-discipline – raising a child who knows what it means to be a good person and behaves that way most of the time. Using a wide variety of these tools will help to teach them how to do this.

Learn More about Time Out

For lots more information and tips for effective time outs, check out the CDC’s guide to Using Timeout, read The Incredible Years or participate in an Incredible Years program. And if you like to know the research behind recommendations, check out: Weighing in on the Time Out Controversy and “The Role of Time-Out in a Comprehensive Approach for Addressing Challenging Behaviors of Preschool Children” (here or here)